1. Statue of Peter the Great after removal, relocated in Kadriorg, Tallinn. 1922. Estonian History Museum.

Every social or political-ideological change is accompanied by a re-evaluation of the physical remains of the preceding era, including the built environment. The concept of heritage, by its nature and history, is closely linked to the concept of nation – both evolved to take on their current meaning in the 19th century. And this process of ‘rethinking’ is destined to last forever. On the one hand, heritage construction demands shaping the image of the selected objects as ours and no one else’s, but on the other hand, it also requires disregarding whatever does not fit ‘our’ identity or national narrative.11. Rampley, Matthew 2012. Contested Histories: Heritage and/as the Construction of the Past: An Introduction. – Heritage, Ideology, and Identity in Central and Eastern Europe: Contested Pasts, Contested Presents. Ed Matthew Rampley. (Heritage Matters 6.) Woodbridge, Rochester: Boydell Press, pp 8–9.

2. Krull, Hasso 1996. Katkestuse kultuur. [Tallinn:] Vagabund.

Even though we have a habit of depicting our past being dictated by an unusually large number of foreign powers, ethnic multitude and sudden political U-turns are in fact characteristic of the history of all Eastern and Central Europe. It is a region that has for centuries been at the mercy of the expansion of German culture and the idea of its alleged supremacy; at the disposal of the power games of the Czarist Russia, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and others. In this context it is – on the contrary – extraordinary how distinctly the ethnic positions and differences can be outlined in Estonia. Due to our geographic location and isolation by the sea, the territorial aspects of Estonian history have been considerably less liable to change than those of several Central European countries.

As a result of the prevailing ‘culture of disruption’2 (which has evolved into a travelling concept in its own right, often far from what the Estonian scholar Hasso Krull originally meant with the term) and due to the numerous changes of the 20th century in this part of Europe, it has often happened that one is faced with heritage and environment that is not desired or valued. Or vice-versa: states and nations have been deprived of something that they consider theirs by right, even as the cornerstone of their identity. In the most extreme cases, and unfortunately also in the recent past, these identity crises have led to war – i.e. to an attempt to take the territory in question (with its population and material heritage) back by force. When it comes to the relative nature of heritage and interpretation, one recalls telling shots from the film Tangerines (2013), where neighbours from different ethnicities reproach each other for their lack of education and gaps in their school system.

In some ways, the need to construct heritage arises from the very multiculturalism of societies – a need for a connecting link, for clarity amidst the abundance and profusion of the wider world. The above-mentioned ‘disruptions’ are never complete – in one way or another, people cope with the remains of the previous eras even in changed circumstances, they continue living among these physical reminders, and perhaps even feel satisfied.

Somewhat to my surprise I have noticed that issues of heritage and rethinking are amazingly ‘common’ despite their theoretical and conceptual complexity – even people not familiar with the discipline of art history or architecture can relate to them with relative ease, and transfer issues across long periods of time, placing the same problems in their contemporary world. Only recently, my presentation on 19th-century renovating practices at a conference in Tartu was followed by a question from a bright city resident, who, with elegant obviousness, brought the discussion to today’s world and directed it to the issue of restoring the late-18th-century stone bridge in the city centre. I later came to understand that Tallinn lacks this kind of a single icon that the entire discussion could culminate in.

To my mind, the scholarly appeal of the topic lies precisely in this ‘popular’ dimension – the contacts between an academic discipline and real life. These inherent contradictions bring into mind the relation of history and contemporary life – to quote the apt title of the famous book by cultural geographer David Lowenthal: ‘the past is a foreign country’.33. Lowenthal, David 2006 [1985]. The Past is a Foreign Country. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. When dealing with the issues of the past, every historian should indeed remind himself or herself why it is necessary to explore these issues at the moment, what is their relevancy and why are they topical. This also means that we acknowledge which issues and emphases we highlight from the past – and more importantly, which ones do we reflect back on the past as researchers.

Destruction and protection have always gone hand in hand in the history of heritage conservation. In fact, it was destruction – especially the devastation that accompanied the Napoleonic Wars and the First and Second World War – that gave rise to the need for heritage conservation as a phenomenon and institution. It is not difficult to find proof of it today, when warfare and deliberate attacks on architectural heritage as the common treasure of humanity are almost a daily staple in the news.

However, the task of heritage conservation is not just protecting objects from evil intentions. Objects in either private or municipal/state ownership are often abused due to insufficient knowledge. Therefore, pedagogic and popularising activities – the fight against ignorance – cannot be divorced from the heritage conservation of laws and punitive measures. In what follows, I intend to look at this popular practice with regard to destruction and its prevention in the context of two instances of establishing an independent state and the following transitional era, with particular emphasis on the idea of Estonian national culture (skipping the reinterpretation in a totally different key that the intervening period also includes: those of Nazi Germany and Communist Russia).

CASE No 1: interwar independence

In the suddenly changed circumstances after the establishment of independent Estonia in 1918, the question about what to do with heritage of foreign origin arose. 4. This article is a concentrate of the following longer studies: Jõekalda, Kristina 2014. „Võõra“ pärandiga leppimine ja lepitamine. Suhtest ajaloolisesse arhitektuuri 1920.–1930. aastatel [Coping and reconciling with ‘alien’ heritage: Debates over the value and protection of historical architecture during the 1920s–1930s]. – Maastik ja mälu. Eesti pärandiloome arengujooni. Toim Helen Sooväli-Sepping, Linda Kaljundi. (Acta Universitatis Tallinnensis. Socialia.) Tallinn: Tallinna Ülikooli Kirjastus, pp 182–245;

Jõekalda, Kristina 2011. Eesti aja muinsuskaitse rahvuslikkus/rahvalikkus. Muinsuspedagoogika ja „võõras“ arhitektuur aastatel 1918–1940 [Nationalism and populism in the heritage protection of inter-war Republic of Estonia: Heritage pedagogy and ‘alien’ architecture in the period 1918–1940]. – Mälu. Toim Anneli Randla. (Eesti Kunstiakadeemia toimetised 20, Muinsuskaitse ja restaureerimise osakonna väljaanded 5.) Tallinn, pp 73–136;

Jõekalda, Kristina 2012. Architectural Monuments as a Resource: Reworking Heritage and Ideologies in Nazi-Occupied Estonia. – Art and Artistic Life during the Two World Wars. Eds Giedre Jankevičiūtė, Laima Laučkaitė. (Dailės istorijos studijos / Art History Studies 5.) Vilnius: Lithuanian Culture Research Institute, pp 273–299.

5. Dyroff, Stefan 2006. Das Schicksal preußisch-deutscher Denkmäler in den polnischen Westgebieten in der Zwischenkriegszeit: Zwischen Akkulturation, „Entdeutschung“ und Pragmatismus. – Visuelle Erinnerungskulturen und Geschichtskonstruktionen in Deutschland und Polen. I, 1800 bis 1939. Hgg. Robert Born, Adam S. Labuda, Beate Störtkuhl. (Das gemeinsame Kulturerbe / Wspólne Dziedzictwo 3.) Warszawa: Instytut Sztuki PAN, pp 271–288.

6. Peetri lahkumine Vabadusplatsilt. – Vaba Maa 2.05.1922 (nr 99).

7. See the sketches and photomontages in Burman, Karl 1924. Iseseisvuse pantheon. – Agu, nr 21 (24.05.), pp 687–690. See also Fülberth, Andreas 2005. Tallinn–Riga–Kaunas. Ihr Ausbau zu modernen Hauptstädten 1920–1940. Köln, Weimar, Wien: Böhlau, pp 110ff; Bruns, Dmitri 1998. Tallinn. Linnaehitus Eesti Vabariigi aastail 1918–1940. Tallinn: Valgus, pp 110–114; Lääne, Margus 2009. Aleksander Nevski katedraali lugu. – Tuna, nr 2, pp 148–156; Ulm, Kalmar. Toompea säravad kuldkuplid. – Postimees. Arvamus 13.06.2009.Despite rather aggressive public opinion and negative attitude, no notable vandalism or systematic eradication of this ‘alien’ (or ‘other’) heritage followed. The burning of manor houses that accompanied the revolution of 1905 has remained a singular malevolent popular punitive action that found its expression in a deliberate plundering of material culture. This was not the case everywhere. In Poland, for example, the same interwar era is characterised by a massive destruction of monuments, allegedly not feeling obligated to act like one of the cultured nations (Kulturnation) that would refrain from restoring so-called historical justice.5

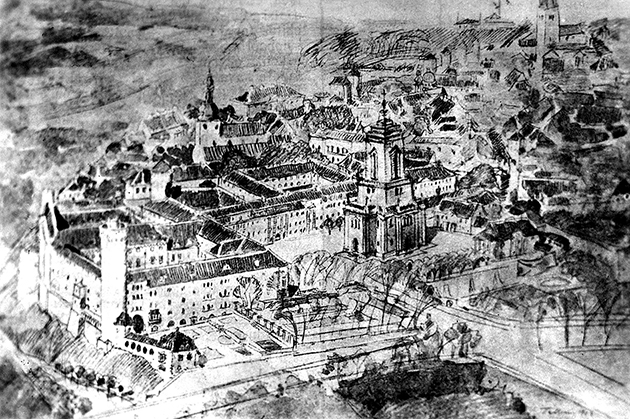

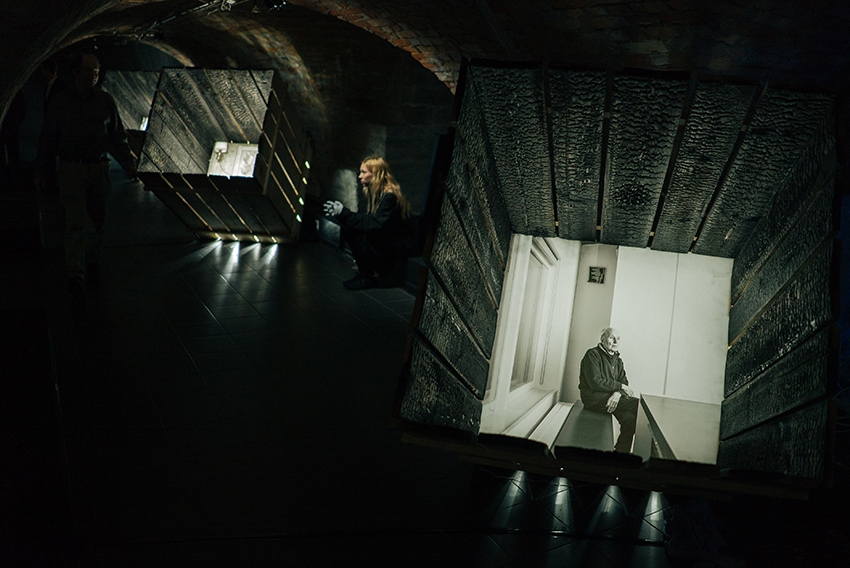

In Estonia, the most blatant symbols of foreign power were indeed removed, but not without hesitation. The statue of Peter the Great (erected in 1910) at what is now Freedom Square in Tallinn was relocated only in 1922, and even then it remained intact (fig 1). A newspaper described the event as follows: ‘when the taking down of Peter was publicly announced, masses began to gather at Freedom Square [---] A crowd of several thousand people filled it from dusk till dawn. Everyone wanted to witness Peter’s departure. The curiosity did not even decrease after the night’s fall, albeit the weather was cool. Most of the crowd spent time mocking Peter. But some reviled the men at work instead – these were the dreamers of a Greater Russia.’6

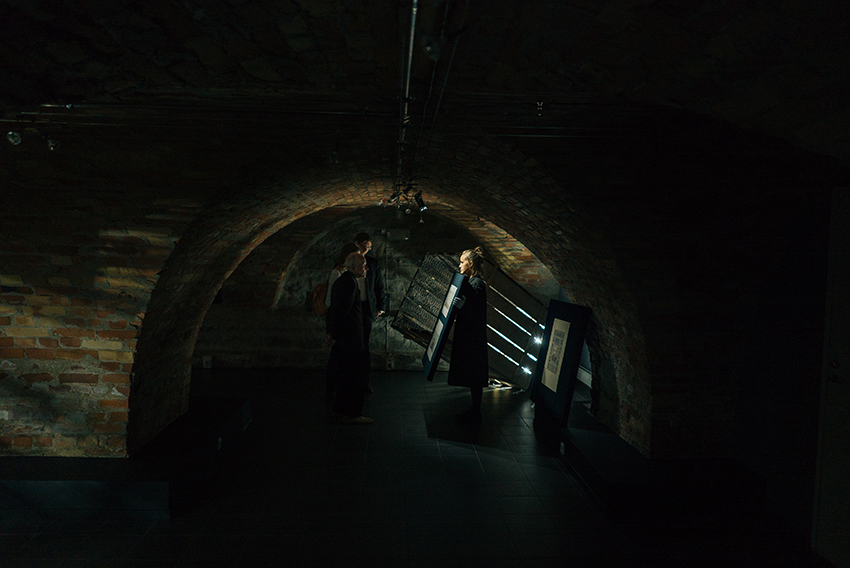

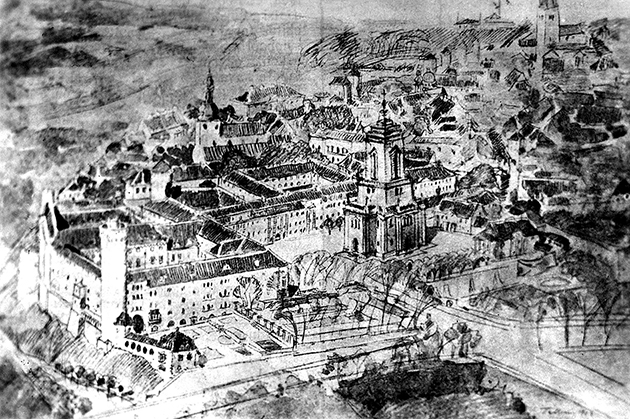

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s another significant public debate took place over the possible destruction of Alexander Nevsky Cathedral on Toompea hill (Domberg) in Tallinn. The architect Karl Burman, for example, presented numerous ambitious designs to reorganise the site into a Pantheon of Independence (fig 2).7 The Russian Orthodox Church, constructed in 1900, is still standing. How did Estonia, as a young and fragile peripheral state, manage to have such an open mind and show such tolerance? Moreover, how conscious was this practice?

2. Postcard with Karl Burman’s design for replacing Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in Toompea, Tallinn, with a Pantheon of Independence. Undated. Museum of Estonian Architecture.

All across Europe, nationalism and active identity construction bred a confrontation between the universal and regional, European and local. Art historians tended to side with those who thought that without the Germans, Estonians would not have been able to even build their own culture. Having one’s gaze turned towards the past and possessing a certain conservative streak, which art history seemed to embody for many on the ‘axis of nationalism’, collided with the progressive spirit of the young state. Hanno Kompus, one of the most active theatre and architecture critics of the first independence period, even went as far as to say that the fact ‘that we have inherited so much from bygone eras and powers’ was a hindrance, which prevented Estonia’s ‘own’ new architecture and the long searched-for ‘Estonian style’ from gaining ground. He claims: ‘unfortunately – and I use this word on purpose – this inheritance of the past is often still in a relatively good, usable condition, so it satisfies our material needs, while abandoning, if not wounding our ideological demands.’88. Kompus, Hanno. Ehitusarhitektuurist [mistake, originally: Esindusarhitektuurist]. – Päevaleht 19.03.1935.

These practical considerations were important indeed in a situation where the state had enough on its table: ceremonial buildings were there, and they could not have been left unused solely because representatives of an ‘alien’ culture had erected them. However, it cannot be said that in the excitement of building a new state and creating original Estonian culture there was no time for posing fundamental questions. Whereas in the context of the 1920s, the open mind in dealing with ‘alien’ heritage was surprising due to the novelty of the situation, by the 1930s, this tolerance could only be maintained fighting active campaigns of nationalisation. State power taking over the government buildings in Toompea or their first national museum buildings (the Estonian National Museum in Raadi, Tartu; the art museum in Kadriorg, Tallinn, that grew out of the Provincial Museum) was therefore a symbolic act. A great number of nationalised buildings brought on urgent work like basic renovations, quickly creating a certain inertia and a number of precedents that were more unequivocally used as justifications for preserving the ‘alien’ structures over the years. Architects also spoke up on issues related to heritage, such as Edgar Johan Kuusik: ‘Should the Old Town [of Tallinn] remain untouched, material commodities will perish, but should new buildings replace old ones, people will be poorer in intellectual values’, and more forcefully: ‘a few more decades of construction in its current form and our Old Town will no longer merit any attention!’99. Kuusik, Edgar 1926. Ümberehitusi Tallinna vanalinnas. – Eesti Kunsti Aastaraamat I, 1924/1925. Tallinn: Eesti Kultuurkapitali kujutavate kunstide sihtkapital, pp 28–29.

In the eyes of Kompus the rather robust medieval architecture took a backseat when compared to the grandeur of Classicism. With his ironic comments on the lack of monumentality of former overlords, however, he seems to put the blame of the poor aesthetic qualities of the Middle Ages on Germans, who introduced this kind of architecture to the Baltic region. He does the same in the case of Historicism and Gothic Revival, calling the following of new trends in late-19th-century manor architecture a vulgarisation of noble Classicism with bourgeois Biedermeier and Romantic styles.1010. Kompus, Hanno. Meie ehituslik pärandus. – Päevaleht 5.01.1935. Naturally, blaming the Baltic Germans for these old-fashioned styles that had indeed become out-dated by the 1930s was convenient and ideologically suitable for him – probably even a conscious demagogic move. It is clear that a historian could not afford such an attitude, but Kompus took the position of a critic. Even today the critic tends to consider historical objects from the point of view of their current context, presentation and reception, while the historian looks at the initial, historical context of the work.

Taking a superior position in relation to the ‘alien’ culture was basically a means of dealing with historic injustice. Aready ten years earlier the painter Ants Laikmaa wrote – by way of a remark, because his aim was to call on people to protect ‘alien’ heritage, to value both old and new simultaneously – that the contemporary architecture of the Baltic Germans is nevertheless old-fashioned and thus ridiculous, cheap and degenerate. According to him, one could follow the lead of Germans, seeing no ideological contradiction there, but Baltic German examples did not simply pass the muster.1111. Laipman, Ants. „Saxa loquuntur...“– Päevaleht 8.09.1925.

So which kind of motivation was introduced in order to preserve ‘alien’ heritage – in addition to building one’s ‘own’ culture? In this regard, striving for the ideal of becoming a Kulturnation certainly became one of the key issues in Estonian public debate, and in this, the readers had to be persuaded that all past periods were indispensable to the present. When it came to architecture, a general conclusion was made that the German heritage is less bad than that of the most recent foreign power. This is well summarised by another quote from Kompus: ‘Our built heritage? From the Germans: mostly soberness, solidity, even dignity, but often dry and dull, bourgeois, even petty and dusty. From the Swedes: little, little, although the little we have is substantial and in good proportions. From the Russians: momentum, grand strokes, effects, but undignified, cheap (and vain about it), not much good – only from the beginning of the last century’. Placing Estonia in the cultural history of Europe – especially being located on the edge of Europe and next to Russia – had been important already for the Baltic Germans. And this is one of the few fundamental questions on which Estonian authors agreed with them.

CASE No 2: post-soviet re-independence

This is a good moment to ask about the universality of these discussions, as these issues can be more or less transferred to another ‘alien’ culture, temporally and spatially, this time in connection with the restoration of independence in 1991. I have in mind the art and architecture of the Soviet period, which to this day elicits a fair degree of nationalist hostility. In recent years, we have hit a wave of celebrating the 25th anniversary of various initiatives and institutions (meetings in the Hirvepark, the Baltic Way, the Singing Revolution, Rock Summer music festival etc). Particularly symbolic among these was Lasting Liberty Day (Priiuse põlistamise päev, when Estonia’s current period of independence as measured from August 20, 1991 exceeded the length of the first, pre-war era of freedom), which provides the point and basis of this comparison. Twenty-five years of independence should mean that the state has left its ‘teenage years’ behind and joined other fully-fledged ‘adult’ countries. As is characteristic of teens, there is plenty of ambition and wishful thinking, but also unwanted veering into both sides of the ‘upheaval’.

During the 1980s and 1990s many European countries witnessed people rooting out and feeling ashamed about the ‘robust’ brutalist architecture from a few decades before. Buildings were systematically demolished – as is often the case when times change. In Estonia, however, the ‘alien’ stigma was added on top of becoming out-dated, which makes it easier to deny and distance oneself. In terms of coping with the Soviet past, an important icebreaker was the opening of the Kumu Art Museum in 2006 with its Socialist Realist section of the permanent exhibition (soon to be updated and reorganised). In the field of architecture, the latest notable attempt in this field was the 2013 Tallinn Architecture Biennial, which carried the theme Recycling Socialism.1212. See the catalogue: Klementi, Kadri; Õis, Kaidi; Tõugu, Karin; Ader, Aet (eds) 2013. Tallinna Arhitektuuribiennaal 2013. Taaskasutades nõukogude ruumipärandit / Tallinn Architecture Biennale 2013: Recycling Socialism. [Tallinn:] Eesti Arhitektuurikeskus. Available here (viewed 21.11 2015).

Cf. Kliems, Alfrun; Dmitrieva, Marina (eds) 2010. The Post-Socialist City: Continuity and Change in Urban Space and Imagery. Berlin: Jovis;

Stanilov, Kiril (ed) 2007. The Post-Socialist City: Urban Form and Space Transformations in Central and Eastern Europe after Socialism. The GeoJournal Library 92. Dordrecht: Springer. This debate was first prominently brought to public attention with the 2007 ‘rebuilding’ (i.e. demolishing) of the Sakala Centre, which had been constructed in 1985 as a new wing of the House of Political Education. However, it is clear from the media that there is still bickering over the Soviet public buildings, such as the Tallinn Post Office, the former tourist shop, the courthouse, the Ministry of Finance etc.

It is well known that the final and swift reconciliation with Baltic German heritage was brought on by the Communist regime: it has been proposed that with a single year of Soviet occupation (1940–1941), public opinion became convinced – on the principle of contrast – that the attempts to come to terms with the ‘alien heritage in previous decades was not an issue to split hairs over. It is difficult to say whether the reconciliation with the Soviet heritage will similarly be channelled into the relationship with new kinds of ‘alien’ culture, e.g. the current wave of refugees. In any case, it is clear that the act of comparison reminds us of the actual diversity of the world. Lively public discussions on the subject are the best cure – although admittedly not always the quickest one.

3. Harju Street in Tallinn, severely damaged in the March bombing of 1944, in the process of becoming a green area; ruins of St Nicholas Church on the right. 1948. Estonian History Museum.

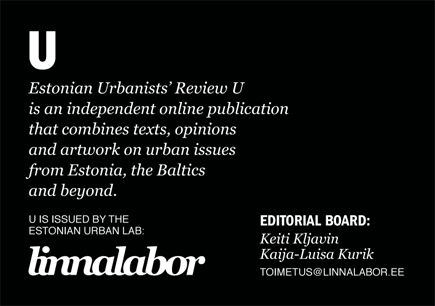

Yet the practice of covering up a problematic past, together with its physical reminders – like the boom of new buildings on the former location of the Berlin Wall – often results in a belated discovery that this layer of history needs to be commemorated after all. This is followed by the digging up of filled ruins, establishing memorial parks or at the very least, adding memorial plaques. The reconditioning of the bombed Tallinn Harju Street is a case in point: the badly damaged former housing area in the middle of the Old Town was redesigned as a green area in late 1940s, this was carried out by means of Tallinners’ compulsory voluntarism (fig 3); after the fall of the Soviet Union the re-opening of the ruins as a kind of a memorial was among the first symbolic steps taken, but overcoming the historic burden resulted in self-victimisation instead; after long debates, the area was again made into a park in 2007, reconstructing only one tiny street, Nõelasilm. The symbolic destruction of an ‘alien’ monument in order to demonstrate one’s superiority can also turn into a farce, and conversely show both blatant non-superiority and the incapacity to deal with the past and its heritage.1313. See also Rampley, Contested Histories, pp 14–16.

14. See also Norman, Kristina 2009. After-War: Estonia at the 53rd International Art Exhibition –La Biennale di Venezia. Catalogue. Ed Andreas Trossek. [Tallinn:] Center of Contemporary Arts, Estonia;

Tamm, Marek 2012. Conflicting Communities of Memory: War Monuments and Monument Wars in Contemporary Estonia. – Nation-Building in the Context of Post-Communist Transformation and Globalization: The Case of Estonia. Ed Raivo Vetik. Frankfurt am Main etc.: Peter Lang, pp 43–72.

15. See Atkinson, David 2005. Heritage. Cultural Geography: A Critical Dictionary of Key Concepts. Eds David Atkinson, Peter Jackson, David Sibley, Neil Washbourne. (International Library of Human Geography 3.) London, New York: I. B. Tauris, pp 146–148.

16. Laipman, „Saxa loquuntur...“

17. Porciani, Ilaria 2010. Master Narratives in Museums. – Atlas of European Historiography: The Making of a Profession, 1800–2005. Eds Ilaria Porciani, Lutz Raphael. (Writing the Nation I.) Basingstoke, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, European Science Foundation, p 7.

18. Rossi, Aldo 1994 [1982]. The Architecture of the City. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London: The MIT Press, pp 130–131, 142. The case of the Bronze Soldier (Alyosha) monument in Tallinn, the relocation of which resulted in street riots of the local Russian-speaking community in 2007, is a telling example of that.14 It must be remembered that although attaching specific meanings to objects of material heritage is simplifying, it does not necessarily mean that nuances are lost in the process. Popular sights can be used to keep the multitude of aspects and different collective memories relevant, perhaps being the most efficient measure of all.15

Conclusion

When it comes to architectural heritage, the material aspect is undoubtedly important because these are real physical remains of the past (even if they have been renovated in the meantime), which remind us who we are and where we come from. This was understood already in the 1920s, when the importance of physical heritage and its central position in terms of identity or image was stressed – this is what the ‘speaking stones’ refer to in the title of Ants Laikmaa’s above-mentioned article.16 In the present environment, the previous eras are visible above all through architecture – in the historical city space the shared past is always represented.

Buildings are impossible to ignore, especially in a dense cityscape, but also in a landscape. Moreover, the built heritage acts differently from the written, oral or visual art heritage because the buildings continue to serve a practical purpose in a later era. Even when abandoned, empty and falling apart, they form an integral part of the built environment. As ruins they might still acquire functionality as tourist sites. This means that although archives, libraries and museums17 certainly have an important role to play in writing history and art history, the documents and artefacts held in them can be forgotten much more easily when times and values change than the architectural heritage.

The city space has been credited with a particularly potent ability to embody the competing memories of different walks of life, nations, genders and, above all, eras. In that sense, the city environment is very democratic. For example, the architectural theoretician Aldo Rossi considers the city itself the collective memory of its residents.18 Obviously, more of value has converged in the cities than in the countryside over time, but at times it seems that the continuous attention paid to the (Tallinn) city space by conservationists and restorers is a sort of escapist gesture. It looks like an attempt to flee from dealing with the problem of ‘alienness’, because in such a multi-layered and multicultural environment everyone values something – that is to say, there are also fewer opponents. In terms of heritage construction, a city attempting to present a unified image has an advantage over a single building or site, because it is inevitably multi-faceted, controversial.1919. Boyer, M. Christine 1994. The City of Collective Memory: Its Historical Imagery and Architectural Entertainments. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London: The MIT Press, pp 2–3.

Thinking about the relations between one’s own and foreign/alien, local and European, old and new, we must note that sometimes issues of the past can offer clearer answers to the problems of the present. On the one hand, this comes from the simplifying and selective nature of history writing, and on the other hand, from the fact that we always (unconsciously) look at the past through the perspective of specific issues raised in the present.

Our ‘alien’ heritage was easier to deal with in the 1920s, because the majority of Baltic Germans had already left or the ones who remained withdrew from public life. It was even easier to come to terms with the Medieval, Baroque or Classicist heritage during the Soviet period, because now all of them were gone and the real threats were totally different. However, this is obviously not a question of temporal distance alone. When you constantly take the position of a victim, it is easy to come to think that everything good comes from within and everything bad comes from the outside. Clearly it is easier to accept destruction that comes from the outside – there is always a culprit; the grief is there but the process is a lot smoother. However, it is much more difficult to deal with unrest brewing within a society – the cases of the heritage of Nazism and Communism in Germany and Russia respectively offer two very different examples of dealing with it. Thus it can be said that Estonia is lucky not to have been in the role of a coloniser in the past: it allows us to look at things in a more relaxed manner now.

Admittedly, ambivalence, abundance and the simultaneous validity of truths are characteristic of any historic reality. However, when it comes to the past we tend to forget this – all the more so the more distant the period. We generally operate with great historic simplifications. We are stuck in historical notions that often paint too unambiguous a picture of the multi-layered reality of past eras, centred around certain topical issues (that are important to the present). In order to avoid being permanently blinded by this, history needs to be rewritten over and over again.