Few questions to the editors of architectural magazines. Mapping the field of Estonian architectural journalism

DIIVAN

Silvia Pärmann, editor in chief

1. What were the specific reasons for founding the publication and on which grounds is the publication operating today?

Diivan (Sofa) is a publication owned by the Ühinenud Ajakirjad Publishers and initially founded by Presshouse. From the very beginning, the mission of the magazine has been to introduce the best product design and interior design in Estonia and we aim to maintain a lifestyle section that corresponds to the values of our readers, introducing restaurants, hotels, architecture and art.

2. What motivates the publishers/editors to engage in this field?

Since Diivan has become the only publication that focuses on Estonian design and interior design to such an extent, it is largely a publication that is created with a small editorial staff and contributors who take an interest in the field.

3. What has been the idea behind your choice of composition/format and how do you choose what you write about? What are the criteria for publishing articles?

Diivan’s selection of subjects has remained unchanged for years, we have found our niche and readers, and plan to stick with design and interior design. We try to find the most topical subjects and the freshest good design, give an overview of products introduced at important fairs and also offer inspiration for people decorating their homes. Articles that meet these criteria and only very high quality photos constitute what we publish in our magazine.

4. Where do your articles come from? How many texts, subjects, objects are you being offered and how many do you ask yourselves?

The articles are mostly written by our two-member editorial staff and a small circle of contributors. We value interior photography of the highest quality and most of our photos are taken by Terje Ugandi, although our regular contributors also include Arne Maasik, Tõnu Tunnel, Kaido Haagen. We find our subject matter in our everyday communication with the professionals of the field; the fairs in Milan and Stockholm are also very inspiring.

5. Who is your reader? What is your print run?

Diivan’s readers are Estonian people with good taste and an interest in design and architecture, there are also many professionals working in the field of design and interior design among them. A large part of our readers are people currently decorating their homes (whether on their own or with the help of an interior designer), however, half of the readership is made up of people who have been following the magazine for years to find inspiration – the public spaces featured in our magazine are interesting even for people who have no plans for a new room at home or at the office.

Our readers are mostly city-dwellers with an above average income. Although on a personal level, we highly value the work of landscape architects, our publication does not cover landscape architecture or gardening – we have left these subjects to our colleagues at the magazines Kodu&Aed and Meie Kodu.

The magazine’s print run is not public.

EHITUSKUNST

Aet Ader, Kadri Klementi – editors in chief

1. What were the specific reasons for creating the publication and on which grounds is the publication functioning today?

Ehituskunst (The Art of Building) was founded in 1981 and back then, it was edited by the architects of the so-called Tallinn School or the Tallinn Ten, headed by Ain Padrik, Ignar Fjuk and Ado Eigi; in later years, Leonhard Lapin was the main editor. Ehituskunst began as the yearbook of the Union of Estonian Architects; younger and brighter architects from design institutes wished to discuss architecture, to publish articles on urban construction, space and residential construction on a mass scale. The name of the journal was borrowed from the book by the same name by Estonia’s first generation modernist Edgar Johann Kuusik, which was published in 1973 and became the handbook of architectural philosophy for the generation.

Today, Ehituskunst is the publication of the department of architecture of the Estonian Academy of Arts and has taken a more academic approach. It is published as per its inception – once a year.

2. What motivates the publishers/editors to engage in this field?

Ehituskunst is a collection of articles, which, to lend a phrase from food culture, is essentially slow food. Articles do not have to be topical, instead they are deliberative; manifestos, essays, academic articles…

3. What has been the idea behind your choice of composition/format and how do you choose what you write about? What are the criteria for publishing articles?

Every issue includes at least one peer reviewed article. So far, we’ve had a theme that connects the articles in some way every year. We select texts that would also be interesting to read in years to come.

4. Where do the articles come from? (How many texts/subjects/objects are you being offered and how many do you request/commission yourselves?)

Every year, we announce an open call for submissions that attracts proposals from Estonia as well as from abroad. We make the selection based on the abstracts we’ve received. The last time we received around ten submissions. However, we often also invite people to write for us.

5. Who are your readers? What is your print run?

Our readership spans from architectural students to pensioners, from philosophers to graphic designers, but it is mainly architects who are interested in more than the mere pragmatic side of architecture. The print run is 500 copies.

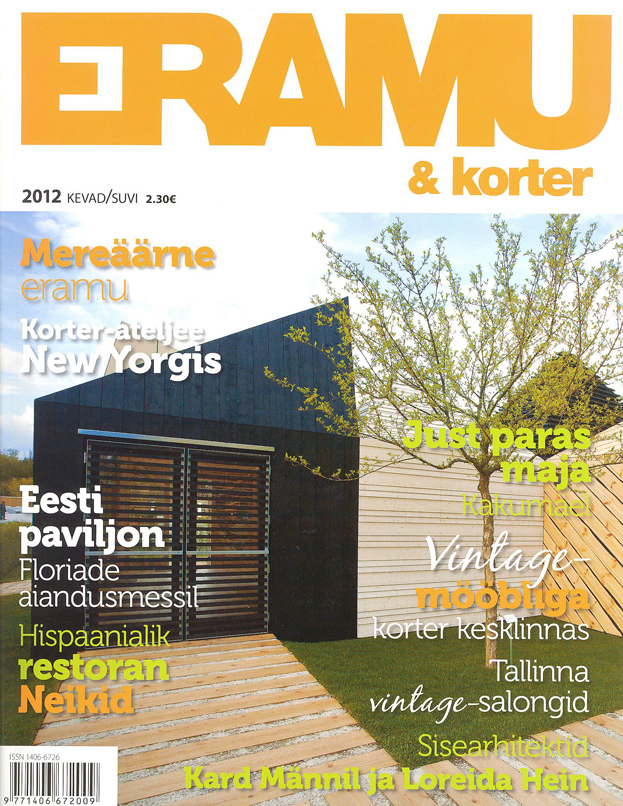

ERAMU & korter

Maris Kerge, the editor-in-chief of the former ERAMU & korter (summer 2013 – spring 2014). The magazine ERAMU & korter went through a makeover in the spring of 2014 and is now published as the architecture, design and interior design magazine IDEE.

1. What were the specific reasons for founding the publication and on which grounds was the publication operating?

Prior to becoming IDEE in the spring of 2014, ERAMU & korter (The Private residence & apartment) went through several transformations. If I remember correctly, it began as a project album. The aim of the album was to introduce fine architecture and good authors to the so-called ordinary people, unlike the magazine MAJA, edited by Triin Ojari, which positioned itself as a publication made by professionals aimed at professionals.

My decision to edit the magazine came from three impulses. Firstly, not unlike the owners of Solness, I wanted to popularise the field of architecture. To demonstrate good architecture on the one hand (I still wonder what the Scandinavians are eating, so that the aesthetic sense of even the ‘average person’ is so good), and to introduce architects as persons on the other hand. Architects are unfairly invisible within society. In addition, I was captivated by the creative potential of editing a magazine, the opportunity to work out the logic of subjects, the structure, to look for stories and writers – to be a theatre producer.

2. What motivated the publishers to engage in this field?

I am motivated to engage in space, both in practice as well as a magazine editor by the conviction that a good space could significantly increase our quality of life. Starting from the logical planning and ending with cosy lighting.

3. What was the idea behind your choice of composition/format and how did you choose what you write about? What were the criteria for publishing articles?

When I started out at ERAMU & korter, a system had taken shape under the editorship of Karen Jagodin: the number of articles, the volume, the aesthetics of the architecture covered, the circle of contributors (writers and photographers) – i.e. the character of the coverage. My preference is for creating a system and sharing responsibility. With ERAMU & korter, I initially mapped the types of articles (a portrait of an architect, a story of the interior design of a specific location, a story on a landscape site, a contemplation on space by a non-architect, etc.) and determined their frequency of publishing (from once a year to once every issue) – while keeping intuitively in mind that the magazine should also give the ‘ordinary person’ an adequate overview of the field of architecture. Secondly, I introduced a board to the publication. It consisted of an interior designer, an architect, a landscape architect, a ‘bystander with an interest in design’ and a person from the field of communications. We worked out the skeleton of the new issue and selected the people and sites to introduce in it.

In parallel with compiling the issues I began a general analysis with communications specialist Kristi Jõeäär to improve the position and readership of the magazine. We mapped the target readership using a focus group, which, for example, revealed that the publication could be a lifestyle magazine.

As previously said, I commissioned articles from the circle of authors established by Karen Jagodin, in the same volume and style. When commissioning an article, I gave the author some keywords to use as the basis of writing, to avoid a retelling of spaces in the style of ‘there is a cupboard in the room, the cupboard is brown’. Since the publishers do not have an editor, I initially proofread the articles myself and then forwarded them to the copy editor. This gave me a very good overview of how people write, who can be asked for an article and who should be ruled out as an author.

4. Where did your articles come from? How many texts, subjects, objects were you being offered and how many did you ask for/commission by yourself?

Finding pieces was a mechanical activity. I first called all my interior designer and designer friends and asked about the work they had done. Then I went through the contacts on the website of the Estonian Union of Interior Architects (I contacted the designers who, according to my intuition, fitted the profile of our magazine). After a year, there were moments when an author contacted me and offered a complete article. There were a few instances where the article or site was suggested by the author.

5. Who was your reader? What was the size of your circulation?

The circulation of ERAMU & korter was 1,500; I do not know the circulation of IDEE. Before me, ERAMU & korter had not mapped its readers, in co-operation with Kristi it was defined as follows.

Target group: 35+ well-off people (net income starting from 1,800 euros per month), who own or are acquiring a second or third home, are interested in high quality interior design, architecture and design that stands out. They are interested in the field and wish to be up to date about novel and versatile solutions. They are looking for information and inspiration from the magazine to freshen up their home, add details or create a new home. The majority of the buyers of the magazine are women, but in the future, we see a 30 percent share of men. Professionally, they are mostly head of small or medium-sized enterprises, specialists or mid-level managers of large companies, esteemed specialists who have attained a sense of security in their profession and are recognised or have made achievements in their field (i.e. a marketing specialist who has won advertising awards, increased the turnover, or other performance indicators). Architecture, culture and design are a counterbalance to their daily business-centered world. The representative of the target group is outward-focused, has a critical mind and is curious and open to new things. It is important for them that good quality culture can be consumed and accessed easily. They know how to enjoy good food and drinks, are prepared to pay a reasonable price for quality. They are intelligent and actively socialise with their peers. At the same time, they are open and friendly to people with a different background. The representative of the target group is socially responsible, but not extreme.

MAJA

Katrin Koov, editor in chief

1. What were the specific reasons for founding the publication, and on which grounds is the publication operating today?

The magazine MAJA (The House) was founded in 1994 by Ado Eigi, Kalle Vellevoog and Enn Rajasaar (AS Solness). Back then, the largely theory-focused black and white magazine Ehituskunst, edited by Leo Lapin, was published under the auspices of the Union of Estonian Architects.

The aim of MAJA was to prioritise coverage of new Estonian architecture and interior design, drawing comparisons with international experience and practices.

Today, MAJA is published by MAJA OÜ, the subsidiary company of Solness Arhitektuurikirjastus OÜ. It is the only publication of the publishing house. To a large extent, the publication of MAJA is subsidised by the Architecture Endowment of the Estonian Cultural Endowment. The board of the editing team is wide-ranging: the Union of Estonian Architects, the Estonian Society of Interior Architects, the Estonian Society of Art Historians and the Architecture Endowment of the Estonian Cultural Endowment all name their representatives.

2. What motivates the publisher to engage in this field?

The wish to build bridges in society and the need to consider space and how it is created, it is a constant process. Certainly, also the wish to promote and professionally analyse the best works of Estonian architects, both in Estonia as well as internationally, which is why the magazine is largely bilingual – the main articles are published in Estonian as well as English.

3. What has been the idea behind your choice of composition/format and how do you choose what you write about? What are the criteria for publishing articles?

The format of the publication comes from the need to develop specialised and critical thinking (our main target group are professionals), but also to improve social cohesion in a broader sense (all readers). The structure of every issue stems from a currently relevant main theme, both in terms of critical thematic articles as well as projects that have been chosen for coverage.

4. Where do your articles come from? How many texts, subjects, objects are you being offered and how many do you request/commission yourselves?

In my experience, all articles have been commissioned so far – they are carefully selected and considered pieces. We are also offered material from time to time, but these articles are usually put on hold indefinitely, because their subject or approach are not relevant at the given moment.

5. Who is your reader? What is your print run?

I do not have any specific statistical data, but to my knowledge, our magazine is mostly read by professionals: architects, architecture critics, but also more knowledgeable subscribers and enthusiasts with a broad outlook. The print run is currently 1,000.

MÜÜRILEHT

Helen Tammemäe, editor in chief

1. What were the specific reasons for founding the publication (or the section dedicated to space) and on which grounds is the publication operating today?

The idea to create an urban section in Müürileht (The Placard) was born because every cultural publication worth their salt should have a section for architecture. There came a moment when urban studies and urban space became a subject of active discussions in a broader context. It was clear then that our sphere (where Müürileht operates) needs a platform like that. At the same time, many people dealing with these subjects appeared and a distinct new discourse in need of an outlet was born.

2. What motivates the editors to engage in this field?

Something is always happening in the city, there are always opinions on that and it is good to read about it. The city is also a location and an engine, a part of the process, influencing it and being influenced by it.

3. What has been the idea behind your choice of composition/format and how do you choose what you write about? What are the criteria for publishing articles?

We try to match the articles on architecture to the rest of the paper, but it is not a strict policy. The coverage depends on the writers and what they feel passionate about. Since we obviously cannot commission pieces (we have no funds for paying writers’ fees), it is difficult to implement investigative journalism in urban issues.

However, there are exceptions when a location or event is a special focus of attention, for example the plans of Kultuurikatel – the piece by Francisco Martínez is the most read in Müürileht!

4. Where do your articles come from? How many texts, subjects, objects are you being offered and how many do you ask yourselves?

Since Veronika Valk was so competent in her niche, me as the editor-in-chief usually never saw the articles on urban issues. They were usually sent directly to her and she decided what was suitable for publishing (whether for us or Sirp, she used to be an editor in both). She was recently chosen as the advisor on architecture and design at the Estonian Ministry of Culture and this would have created a conflict of interests. This is the reason we currently have no editor of the urban section and it is sorely felt. From the March 2015 edition onwards, Sille Pihlak is editing the section on architecture, but her field of specialty is architecture, not urban space in the broader sense.

5. Who is your reader? What is your print run?

Our reader is intelligent, up to date with trends, innovative, open, unprejudiced, with a broad outlook, emphatic, usually has a higher education or is in the process of getting one.

Our print run is 4,500, and 700–800 of it are shipped to shops and subscribers – the rest is distributed to new locations every time, according to the new system. Instead of being available for free, the paper is now on sale, but since it is difficult to organise selling in the previous places of distribution (entrance halls, schools, lounges, galleries), we are more dependant on conventional sales through Lehepunkt. To be more visible and available, Müürileht can be found for free in locations where we would be most likely to be picked up by potential new readers. For example, we gave away a part of our last print run to universities and upper secondary schools, next time the paper could be distributed in public transport or some smaller towns – depending on specific events taking place and the relevance to the issues covered in the paper.

SIRP

Merle Karro-Kalberg, the editor of the architecture section

1. What were the specific reasons for founding the section dedicated to space and on which grounds is the section operated today?

The cultural weekly Sirp (The Sicle) began regular coverage of the built environment in 2010. In these five years, the paper has had three architecture editors: Margit Mutso, Veronika Valk and currently Merle Karro-Kalberg. Architecture affects our public space and therefore, the issues of the built environment are no less important than the issues of art, theatre or cinema. In 2013, during the so-called Sirp scandal, architecture as a section disappeared for a few issues, but after Ott Karulin became the editor-in-chief, the continuity was restored.

2. What motivates the editors to engage in this field?

Sirp is the only publication in Estonia that consistently covers issues related to the built environment and design every week, without the burden and hassle of writing project applications and reports.

3. What has been the idea behind your choice of composition/format and how do you choose what you write about? What are the criteria for publishing articles?

Since Sirp is published weekly, we can react quickly to bring current affairs to the readers. According to the format of Sirp’s articles, important issues can be covered more extensively and in-depth. The subjects of Sirp are usually assembled around the keyword of the issue (for example Audience, Copyright, Awards) which also moulds the choice of articles. A good Sirp article should be a dense enjoyable text that not only conveys the idea but is also a pleasure to read. Admittedly, it is very difficult to publish texts in the field of architecture that would speak to architects and film critics alike. Pieces that go into the details of the built environment will not engage specialists of other fields. Articles that are eagerly read by others are boringly superficial for people who have an in-depth knowledge of architecture. Finding a balance is a challenge.

4. Where do your articles come from? How many texts, subjects, objects are you being offered and how many do you request/commission yourselves?

The majority of texts are commissioned, offers of contributions are rarer.

5. Who is your reader? What is your print run?

The readership of Sirp is very wide on the one hand, encompassing musicians, public figures, theatre critics, filmmakers, architects, etc. On the other hand, there is a small circle within that readership that appreciates a dense and good text, can think along and is interested in the relations of culture and society. The print run of Sirp is 5,000.

ESTONIAN URBANISTS´ REVIEW U

Kaija-Luisa Kurik, Keiti Kljavin, Andra Aaloe – editors in chief

1. What were the specific reasons for founding the publication, and on which grounds is the publication operating today?

Linnalabor (Estonian Urban Lab) began compiling the Urbanists’ Newsletter U in 2010. The initial aim was to send the newsletter via e-mail every two months to cover important events in the field, and also to publish longer theoretical and deliberative texts and urban photography. Largely thanks to the enthusiasm of the editors, the newsletter gradually grew into a voluminous online magazine, which increasingly focused on theoretical issues. Renaming the newsletter as a review in 2012 expressed this shift of emphasis in terms of content. The pdf file published six times a year has become a bilingual and rather voluminous online review published twice or three times a year. The content of the review takes shape according to the intuition of the editors and in the form of special issues. The interdisciplinarity of urban studies allows us to delve into visual, social as well as strictly spatial issues and therefore the enthusiasm is still there.

2. What motivates the editors to engage in this field?

Publishing U depends on a rather wide circle of people, and as editors we are glad that we have directed the visuals, programming, translations and language editing in the hands of professionals. The editing team of U has a background in Urban Studies at the Estonian Academy of Arts and the motivation comes from the wish to promote the subject, delve into interesting issues, start a discussion and create networks. Even though U's appearance is rather clear-cut, we try to defy boundaries (state- and speciality-wise) – with each new issue we redefine our positions, the team is international, U has gained its own readership and list of contributors outside of Estonia.

3. What has been the idea behind your choice of composition/format and how do you choose what you write about? What are the criteria for publishing articles?

U is published in special issues – we have focused on the broader theoretical structure (for example, special issues on peripheries and post-socialism) as well as specific cities (we have published special issues on New York, Berlin and Helsinki). Special issues are usually connected to topical events (for example, the special issue on the post-socialist city was published in connection with the Urban and Landscape Days). We have no criteria as such, because the articles are born voluntarily and since we cannot pay any fees to our authors, the editors put more effort into finding and persuading contributors, and later into editing texts and giving feedback.

4. Where do your articles come from? How many texts, subjects, objects are you being offered and how many do you request/commission yourselves?

U’s articles are born both as commissions as well as submissions. Several authors have studied, or are still studying subjects related to (built) space at university, are linked to U’s publisher Linnalabor, or other urban-related events in some way. U is also involved in republishing and translating articles, thus bringing urban theory closer to the reader and contributing to the urban studies vocabulary in Estonian. We also exchange articles with Müürileht and other independent publications. In recent issues especially, the principle of collage has clearly emerged – U is less and less a topical newsletter and is increasingly involved with drawing together the main issues of the field and posing questions.

5. Who is your reader? What is your print run?

U is an online publication, which is also available as a PDF and can be printed out. U has mapped its readership few years ago and found its average reader is aged 24–29, usually female, but coming from very different fields: local government officials, urban activists and researchers, freelancers or from the private sector, also a lot of students. In addition to being published online, U also appears on paper in co-operation with various partners (for example U15 (a special issue of Linnaidee (Urban Idea initiative), U16 (in co-operation with the Urban and Landscape Days) and the current issue, U17 (in co-operation with ÕU Magazine).

ÕU

Merle Karro-Kalberg, Anna-Liisa Unt, Karin Bachmann – editorial board

1. What were the specific reasons for founding the publication and on which grounds is the publication operating today?

The impulse to create the publication came from the lack of specialised texts in Estonian that would go beyond the everyday decorative gardening when covering the field. This demand has simply not been met by today, on the contrary – it has increased; we have a readership; and areas and angles worth introducing and opening up keep appearing. A couple of issues have usually been prepared in advance in our minds. Initially, we were published as the magazine of the Estonian Landscape Architects' Union, however, later it seemed that it would be easier to function as a separate non-profit organisation. Today, ÕU (The Yard) is published by the non-profit organisation Kino, and a circle of friends that we spend a lot of time with anyway, fill in as the team and editorial staff. We have no board of experts.

2. What motivates the editors to engage in this field?

We have developed a system, we don’t have the heart to stop now, at least we have not really considered it seriously (we do have doubts sometimes – ÕU sometimes lags behind our other projects and we don’t want to work half-heartedly). The magazine has fostered discussions, demonstrated what we do to anyone who is interested, trained the citizens to be up to date, to be critical and demanding, but also more lenient, obliging, open-minded. Looking at the increasing row of issues of ÕU on the shelf, we are happy about the texts and authors who we have urged to think about outdoor space.

Whereas the first issues were published with virtually no budget, we are now motivated by the fact that the Cultural Endowment considers our publication important enough to lend its support.

3. What has been the idea behind your choice of composition/format and how do you choose what you write about? What are the criteria for publishing articles?

The physical format was formed according to the wish to fit the magazine in a pocket or purse. Every issue is published in a single colour (a chosen tone) print, with a full colour print sheet in the middle of the magazine. The content is founded on sections that find their names and titles when the texts are coming together. We have tried to keep a balance between theory and practice, when the subject allows it, and in addition to thinkers and opinions we have also introduced completed projects. The theme of the issue is formed as a combination of relevancy and the preferences of the editorial staff at the given moment. We have tried to turn the covers of the latest issues of ÕU into a multi-purpose advert/calling card – for example, a foldable model or ruins (the latter by the illustrator Ulla Saar), a contour map to be coloured, etc. We would like to keep including visual artists in the making of the covers to give their work a boost. The criteria for publishing articles is quality – the text has to be written well and correctly and must contain adequate information. It should be a good read.

4. Where do your articles come from? How many texts, subjects, objects are you being offered and how many do you ask yourselves?

We sent a call for submissions to the Estonian Landscape Architects' Union for the first issue, but since the circle of specialists of the field (who write) is quite small, this method did not justify itself for long. Every issue is framed by a broader subject and for this, we turn to authors ourselves, to put together a good set of writers. We have also commissioned articles from geographers, writers, historians and other people outside of our specialised field, to avoid getting stuck in our habitual tastes and methods. People offering us contributions is more of an exception.

5. Who is your reader? What is your print run?

We were first published in the framework of the international landscape architecture month as the publication of the Estonian Landscape Architects' Union in April 2009; the issue was rather experimental and the print run was 1,000. From then on, the print run has been 500. Our readers are specialists in this field and associated fields and also people who take an interest in outdoor space in general.

Challenge near the Rakvere castle. August Künnapu

Challenge near the Rakvere castle. August Künnapu

.jpg)

Photo: Kaja Pae

Photo: Kaja Pae

Urban and Landscape Days XI, 2014.

Urban and Landscape Days XI, 2014.