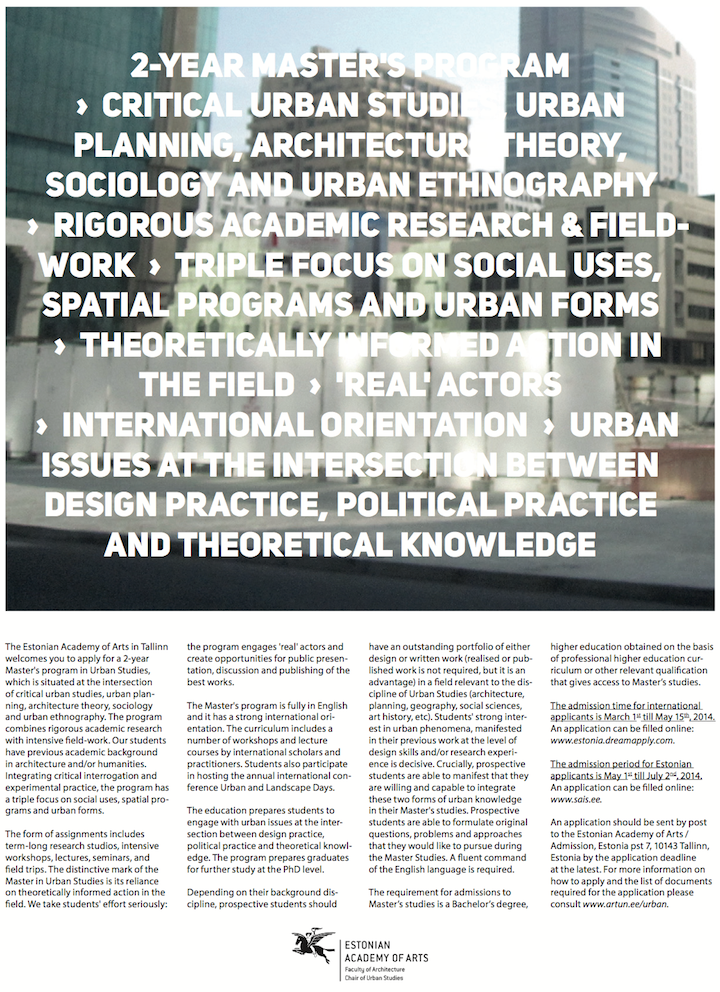

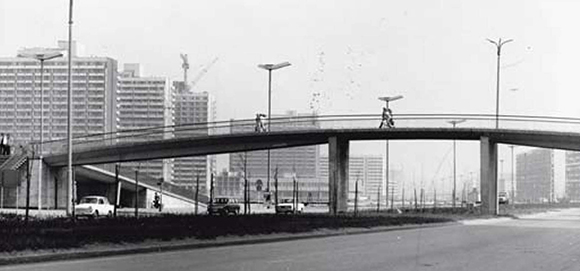

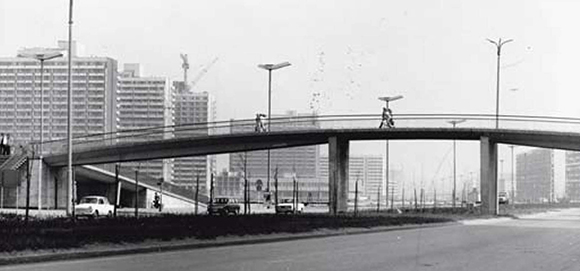

The old must give way to the new – the centre in Halle (Saale) in the mid-1980s as well as in 1969 when the village of Passendorf fell victim to the urban extension of Halle-Neustadt.

This article was first published in a catalogue of the DAM (German Architecture Museum), 2010/11.

‘capitalist city – term used in the world of liberalism,

profit-making and the power of capital;

socialist city – term used in the world of socialist democracy

and the power of the people.

Construction is synonym with learning process!’

Notes from a Dresden Technical University lecture course on urban design, 1982

We’re somewhere in East Germany in the year 2007. The bronze bust of Wilhelm Pieck which once stood in the suburbs, has been replaced by rustic wooden benches on which school children eat their sandwiches during breaks. They know they have heard of the first GDR president, but don’t remember exactly what it was. In the city centre, ten-storey 1960s housing blocks are being sold and will have to make way for the huge shopping centre projected by a property developer for this site. Prior to demolition, the blocks have been veiled in painted lengths of textile material, gaudily colourful shrouds so to speak. These buildings – erected with total disregard for and contrary to the historic urban fabric, had yet been full of everyday life and certainty of the future. They were meant to demonstrate the unity of industrial construction and socialist architecture and to ‘differ fundamentally from the chaos spreading in the centres of capitalist cities…’11. Walter Ulbricht, Städtebau und Architektur. In: Deutsche Architektur, 8 (1959), vol.12, p. 646., as Walter Ulbricht put it. However, architects of his time only gave them a condescending smile.

The political and ideological, economic and social framework conditions for the socialist city no longer exist. In this sense, it is dead and only lingers on in architectural fragments as souvenirs of recent East German history, some of them as pieces of evidence of modern urban planning, but even more as extremely endangered heirlooms of an historic experiment that has been declared a failure. And yet – though the debate on the qualities and deficits of the socialist city (if it happens at all) is mostly concerned with three-dimensional examples (e.g. in cases where an ensemble of GDR modernism is threatened with disappearance), it is not only a discourse on enclosed or built-up space, but also touches on the very character and foundations of society. All talk of giving up the socialist urban model therefore also means the dismantling of socialist ideals. People have rejected these, at least temporarily, and found them generally unsuitable for shaping the design of a new societal order and its structural expression.

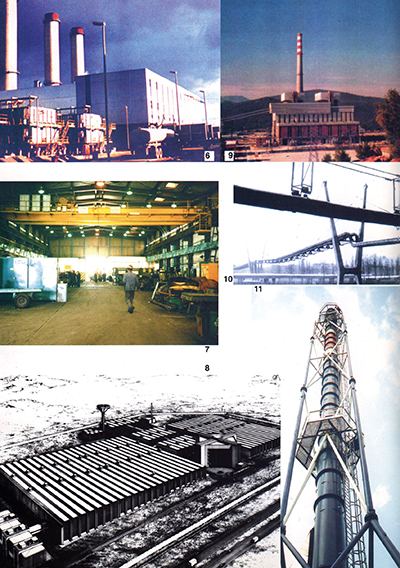

A brave new world in the making: Halle-Neustadt in the 1960s

THE CITY AS A BUILT MODEL OF SOCIETY

The socialist city is regarded as the attempt to translate a societal model into built space. It may be understood as the architectural-ideological answer to political, economic and social/societal problems. In a free interpretation of socialism22. See Thomas Noetzel, Sozialismus. In: Metzler Philosophie Lexikon, Begriffe und Definitionen, p. 484, 1996. (English: See Encylcopedia Britannica, vol. 23 Macropedia, pp. 535 ff. on Marxism, and vol. 27 Macropedia, pp. 393 ff. on Modern Socio-Economic Doctrines and Reform Movements. 15th edition, London etc., 1997.

3. The ‘Sechzehn Grundsätze des Städtebaus’ and the ‘Aufbaugesetz’ (both 1950) were two of the three resolutions the GDR government passed on building on its ter- ritory. The third resolution was the ‘Beschluss zur Industrialisierung des Bauens und weiteren Entwicklung der Typisierung’ (Resolution on the Industrialization of con- struction and the further development of serialization, 1955).

4. See Simone Hain, ‘About Confectioners of Towers and Bakers of Rye Bread: The Built Environment of the GDR’. In: Two German Architectures 1949 –1989 (exhibition catalogue), ifa Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen, Stuttgart, 2004, pp. 26 –39., one might therefore see it as a three-dimensional model of a just distribution of national economic riches, as promoting social cohesion, restraining processes of individualisation, warding off individual and social alienation, eliminating political powerlessness and curbing unrestricted private ownership and right of disposal of means of production as well as real estate.

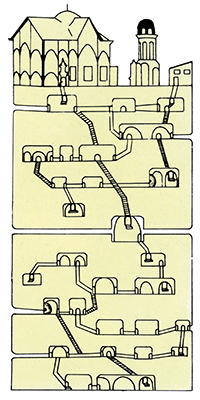

The experiment begun in East Germany after World War II consisted in developing such a design. Political decisions3 laid the foundations for this, formulated among others in the ‘Sixteen Principles of Urban Planning’ and the ‘Reconstruction Law’, which regulated society’s – the people’s – right of disposal of property. Over forty years, the attempt at substantiating Marxist-socialist philosophy through building produced a number of different models. The idea of the socialist city is therefore now associated with the reconstructed and restructured war-destroyed centres of Dresden or Magdeburg, with the new city of Eisenhüttenstadt or urban extensions in towns such as Hoyerswerda or Schwedt near big industrial centres, and– not least – with ‘The Slab’, as the large-panel housing satellites in or outside big cities were called (e.g. Berlin-Marzahn, Halle-Neustadt, Leipzig-Grünau). The socialist city – that is parade grounds and metre-high stone fists, but also the infant day-care centre in the former villa of an upper middle-class factory owner.

Though the architectural designs were partly similar in both East and West Germany, they differed in terms of the conditions under which they were produced, and in the ‘identities’ created through them. What distinguished the socialist city positively from West German or West European cities, was not only the aesthetic guises of East German architectural modernism, but above all designs that – in terms of structure, space and philosophy – were directly linked to the political system.

For one thing this offered the chance to build on state- owned and therefore often vast sites, without having to pay free-market-controlled property prices, and to do this through politically initiated and centrally planned processes. For another it represented a thinking which could be called idealistic: faith in the power of the collective and in the need for subordinating individual interests to those of the community; equality for all and the desire never to lose sight of the welfare of society as a whole. Even though it was almost impossible to translate these ideals into reality, they took root in people’s minds and contributed considerably to people’s sense of identity, albeit a ‘reflexive’ self-understanding, critical consciousness4 marked by doubts, which resulted from constant comparisons between East and West Germany, between ambition and actual achievement. After all, the reality of the socialist city included a good deal of short supplies and arbitrary acts of central planning authorities.

Dismantling of ideas after reunification, here of the sculpture ‘The Fists’ on Riebeckplatz (Ernst Thälmannplatz in GDR times) in Halle (Saale), 2003.

CHANGED COMPLEX OF PROBLEMS

With German reunification, the increasingly felt political and economic helplessness of socialist experimenters first ended in general perplexity and want of concepts on the part of East German politics, which also spread to other areas of community life. The rejection of political despotism and the misguided developments it initiated, among them economic and ecological developments, again ended in the ‘chaos of the capitalist city’. Only much later were the urban redevelopments during the first years after reunification to be seen as a social and historic-political patchwork which did have qualities, but at a time when buildings and spaces were already lost.

Changes in political ideas are generally carried forward by replacing leading persons in communal administrations. The new old ideal of the European city was to be the heir of the socialist city, with the ‘Planwerk Innenstadt Berlin’ (Planning Work Inner City Berlin, 1996) as godfather. This proposal, all too often misinterpreted as a spatial plan, served as a guiding motif for urban design, supported in its credibility by the fact (rightly lamented by East Germans at the time) that the GDR had almost totally neglected the historic centres of its towns and cities. The typical European city is a city whose inhabitants – as the owners of its small-scale properties – self-confidently take an active part in determining its fate, but in the GDR, after forty years of socialism, the political and economic foundations of this type of European city had disappeared.

Yet long before urban design concepts are geared towards rearranging urban spaces, it is the question of ownership, in conjunction with political and economic structures, which determines the appearance of our cities. The Kohl administration created tax depreciation programmes to mobilise West German capital for the ‘Reconstruction East’.5

Housing blocks ‘Am Brühl’, Leipzig, from the 1960s and in early 2007, when blocks were artistically wrapped by Fischer Art to draw public attention to this ensemble. The wrapping was unsuccessful, as the redevelopment project requires the demolition of the old buildings.

5. After reunification, the German government introduced the Special Tax Depreciation East which enable property buyers to apply for a 50 per cent depreciation on the buying price, including subsidiary costs and freely allocable over a period of five years.

6. A total of about 2.1 million cases of restitution claims were filed. See Joachim Tesch, Klaus-Jürgen Warnick, Staatliche Wohnungsversorgung und kapitalistischer Wohnungsmarkt. In: BdWI Forum Wissenschaft 2/2004.

7. In the GDR, the construction of new housing blocks was funded via long-term loans from the GDR state bank. Amortisation and interest rates were not paid by the housing companies, but by the communes and the state budget respectively. Following the end of the GDR and the privatisation of its state bank, accounting balances actually turned into a mountain of ‘old debts’ which housing companies now have to pay back to commercial banks. On average, every new flat in East Germany was burdened with a debt of DM 15,000. This meant that, on entering the new market economy, East German housing companies were in fact bankrupt. – See Matthias Bernt, Fiktive Werte.

8. However, birth rates in Germany of 1.32 (east) and 1.37 (west) are still fall below the rate of 2.1 children per woman, necessary to maintain present population figures.In a certain respect, these triggered the closing- down sale of the socialist city. Every construction project benefited, indiscriminately, from the garage for two cars to the shopping mall. In the early 1990s, the maxim ‘restitution before compensation’ led to many protracted disputes (often decided through court proceedings) between former and present owners or among communities of heirs.6 This is why empty lots and buildings in the city centres could not be sold for a long time and blocked urban redevelopment and spatial planning (and some are still unsold today). Often the new private proprietors no longer come from the city itself or from East Germany, and ownerships multiply when old residential buildings are divided into marketable 60-square-metre condominiums.

Larger sums mostly go to the suburban ‘intermediary city’ where properties are to be had more easily and cost less. Inner-city spacious residential ensembles are no longer profitable; urban spaces are again meant to be cosy and comfortable, instead of transporting ideas or setting up ideological signs. Enormous over-production is rampant as regards all types of buildings. The sites of the large council housing estates, however, still the property of municipal housing companies, burden communal budgets with great numbers of buildings in disrepair and burdened by old debts.7

At the same time, the apparent individualisation, i.e. private ownership and development, of the country’s built environment – for forty GDR years unwanted and restricted – led away from socialist times and brought forth a class of new proprietors which – for its size in numbers – moves to the wrong place, to the urban surroundings. In contrast to developments in West Germany, suburbanisation in East Germany contributes greatly to inner-city buildings losing residents on a massive scale and to serious demographic and economic urban shrinking processes.

Almost over night, the former workers’ and peasants’ state becomes a structurally weak region with high unemployment and ‘economic refugees’. People all over the country moved to where they found work in the few centres of economic power. This meant that many East German city centres became patchworks of islands of growth and shrinkage amid increasingly extensive ‘areas under observation’. The East German exodus was accompanied by natural losses of population: while before 1989/90, birth rates in East Germany totalled a statistical average of 1.9 children per woman and sometimes san below 0.8 after that. At present, figures are on the rise again, but birth rates in East Germany are only slowly adapting to those in the western German states.8

Misguided developments in the 1990s: suburbanization of the surroundings and a leap in scale in Leipzig itself.

REALITY AS A RESOURCE

Due to the factors mentioned above, there are more than 1.3 million empty flats all over the eastern federal states. The problem of housing the masses – an old social issue and demand of the workers’ movement – has thus practically solved itself by itself. It took some time for the phenomenon of empty flats to filter into public consciousness at the beginning of the new millennium, not least owing to younger architects and urban planners who understand the interdependence of social and spatial developments as a whole and are starting to formulate new theoretical models for new urbanist situations.

Kolorado Neustadt99. Markus Bader, Christof

Mayer: Kolorado Neustadt. Aktive Diversifizierung und situative Praxis im Stadtumbau. In: IzR 3/4 2006 – Stadtumbau in Großsiedlungen, Bonn, 2006.

10. Urs Füssler, Das Carambole-Prinzip, Arch+, no. 166, Aachen, 2003, pp. 16–24.

11. L21: Kern & Plasma. In: Schrumpfende Städte, vol. 2 – Handlungskonzepte, pp. 220 f. Ed.: Philipp Oswalt, Ostfildern-Ruit, 2005.

12. Christopher Dell: Prinzip Improvisation, Cologne, 2002., the CarambolePrinciple10, the Core Plasma Model11 or the Improvisation Principle12 are all examples of new spatial and social models dealing exclusively with existing structures and calling for an non dogmatic approach to the urban everyday. These models propagate the principle of a pragmatic ideal city. All of them imply criticism of rigid traditional notions of space which, due to the fact that cities are increasingly ‘punctured’ by gap sites, are beginning to adapt to those spatial concepts of classical Modernism, albeit in a strange new way. Space is about to flow again, this time without any politico-ideological superstructure. The unintentional amnesty for open, modernist spatial images is based on processes of shifting and concentration in a ‘globalised’ world. Looking at the present demographic and economic situation, it seems very unlikely that a general equality of living conditions will ever be achieved. Planners must therefore try to qualify differences and organise exchanges between the different spaces. Planning can no longer only be concerned with built space, i.e. architecture, but will also have to deal with creating and ordering spatial relations, i.e. social space. Here communication plays an essential part and, in a certain way, returns to the aspect of reflection about the relationship between the individual and the community, about the state of society as a whole which is closely related to the state of our own ‘good life’. Recent theories therefore aim for flexible, changeable spaces which embrace both cultural and participatory practices. The city of tomorrow is not the construct of individual artistic architects, but must be permanently adaptable and negotiable.

Conflicting spatial images herald the emergence of complex, global networks and relations, but also of pluralism and freedom in this new age. At the same time, these images require partially changed habits of perception (just like the ‘intermediary city’ does) for their beauties to be discovered. Exciting urban-and-rural collages cannot be had just like that, they are not easily transmissible and even less easily translated into reality. Money is always scarce and another obstacle is the lack of consciousness and the will to distribute public funds purposefully and to monitor how they are used.1313. While communal, federal state and central governments together spent 2.6 billion euros of public funds in eight years on the ‘Urban Restructuring East’ programme, the German government, in the same period, paid out roughly 80 billion euros for the so-called Eigenheimpauschale, or owner-occupied home lump sum subsidy, which supports the construction lobby and middle-class citizens, but contributes to ‘urban sprawl’ in the countryside and to depopulating inner cities. See Philipp Oswalt’s introductory essay in: Schrumpfende Städte, volume 2 – Handlungskonzepte, p. 13. Ed.: Philipp Oswalt, Ostfildern-Ruit, 2005.

14. In Saxony, for example, 80 percent of the programme’s funds are used for demolition work and only 20 per cent for urban revitalisation. In addition, the funds provided by the ‘Urban Restructuring East’ programme are in fact mostly used to fend off bankruptcies of communal housing corporations or to demolish redundant buildings, and only to a minor extent to revitalise and enhance urban areas.14

The Carambole Principle: As if the reality of the city could be distorted just a little by the notions it inspires. Photo: Urs Füssler, 2003.

On the other hand, existing property rights often block the use of empty sites for public purposes. The site border represents the invisible, legal barrier and with it perhaps the most important political task. Without giving citizens the chance to acquire and utilise empty sites and buildings, the potentials of ‘shrinking cities’ will not be able to unfold. Initially debated measures, such as a progressively rising property tax, revaluation of properties in line with current market conditions or property exchange pools are no longer an issue in the official public debate. The example of Leipzig and other cities, which made private properties available for temporary public use via so-called allowance contracts, have been the exception. The city continues to belong to the land register and the (sometimes cooked) books of the property owners.

Of course, even global capital has discovered Germany, and here mainly the low-cost East German property market. Today you may learn of the existence of a new owner, and tomorrow you will hear that the house, company or hotel chain has again changed hands and now belongs to yet another investor. In these regions you will be able to buy an entire street block for the sum a residential and commercial block-cost in one of the large European agglomerations. In what way the development of property portfolios will affect urban development, remains to be seen.

With the return of the capitalist society, the nature of a village, town or city is again determined by marketability. We must not let them be reduced to this quality alone. For ‘the good life’ we urgently need the relics of the socialist city – and not only its spacious public squares and iconic buildings of the 1960s. The least we need is reflection on and questioning of the role of private ownership and the discussion of social cohesion. The post-socialist city is like a seismograph that indicates future developments and, just like its predecessor, remains a testing ground.

VEEB wide copy.jpg)