MIXTAPE OF CLUBBING, GENTRIFICATION, BIG MONEY, ANGRY PEOPLE & POSSIBLE ALTERNATIVE FUTURES

REGINA VILJASAAR, urbanist, Linnalabor, Tallinn & JÖRN FRENZEL, strategic designer/architect, Vatnavinir, Berlin

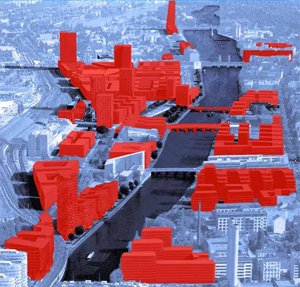

'Fuck Off Mediaspree' and new developments. Photo: Regina Viljasaar

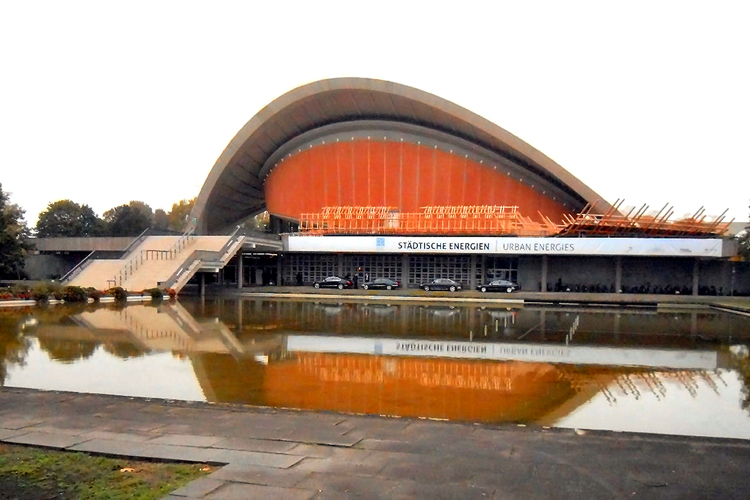

The seed of this article was planted in November 2012 when on a Monday morning we visited the KaterHolzig club in Berlin with a small group of curious urbanists. While the last hazy-eyed clubbers were occupying the courtyard and a muffled techno beat reached the headquarters, people behind the club explained to us their concept of a cooperatively-run, fully sustainable live-work-play hub, an experiment that in this scale is probably unheard of. Our desire to understand the project became the starting point for a colourful excursion through the shifts and changes that have taken place in Berlin over the last decades.

1. Bar25 – THE BEGINNING

The site that soon might become a testing ground of new cooperative and economic models was ten years ago ’part of a larger stretch of land along the river Spree owned by Berlin's sanitation service (BSR); they had been having trouble finding tenants for the space, so they were happy to rent a smaller parcel out’11. Luis-Manuel Garcia. 'Showdown in Spreepark'. Nov 26, 2010. That was in 2004 and soon the location became known as Bar25, the embodiment of Berlin's legendary night life.

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 the new Berlin club scene had been very improvised and spontaneous. Fueled by techno music and its many derivatives, the actors eagerly occupied vacant space, then still ample in East Berlin. The clubbing scene and associated social projects22. For example Jamaican cultural headquarters YAAM soon moved into the abandoned industrial sites and vacant lots along the River Spree, found mainly in the Schillingbrücke and Ostbahnhof areas. At the beginning, this all stayed fairly underground, but soon, with Berlin increasingly becoming the It-location in the second half of the 90s and early 2000s, this scene became well known on a worldwide level. This is the time when Bar25 opened.

One of the founders of the club, ’[Christoph] Klenzendorf moved onto the property with a trailer and his friends in August of 2004, and a six-week-long, non-stop party ensued. Over the winter, they started with plans to create a bar, hostel, and restaurant on the location, which opened in the spring of 2005 as Bar25. [...] The six-week party that started it all set the tone for Bar25's events. The place soon became famous for its "anything goes" hedonism and drugged-out messiness. The club would open on Friday and stay open non-stop until Monday afternoon or evening, and so on Sundays it became a favourite spot for people to collapse or keep going at the end of a gruelling party weekend. Everyone has a story of excessive drug use, sexual adventure and/or lost items.’3 3. Luis-Manuel Garcia. 'Showdown in Spreepark'. Nov 26, 2010

During the 90s, the neighbourhoods of Mitte, Prenzlauer Berg and Friedrichshain (where Bar25 was located) had become the ‘cool districts’: new cultural experiments and old East Berlin social structures happily co-existed and gentrification was not yet a widespread term. But a decade later, ’property values were rising along the river Spree in Friedrichshain as the gentrification of Mitte and Prenzlauer Berg was pushing eastward and the urban development plan, ’Mediaspree’ was accelerating.’4 4. Ibid.

The growing fame of Berlin as an ‘alternative city’ and the subsequent exposure to ‘global capital interests’ kicked off the same merry-go-round of gentrification as everywhere else in the Western world. This development put increasing pressure on places such as Bar25, whose relationship with the landlords had never been friendly, eventually forcing them to find alternative locations – although sometimes still nearby.

TAKE A STEP FURTHER: Read an adept overview of Berlin ́s urban renewal, gentrification and the effect of tourism HERE.

MORE ON GENTRIFICATION AND BERLIN from Monocole.

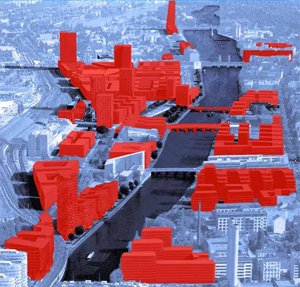

One of the pictures circling online that depicts the volume of Mediaspree development.

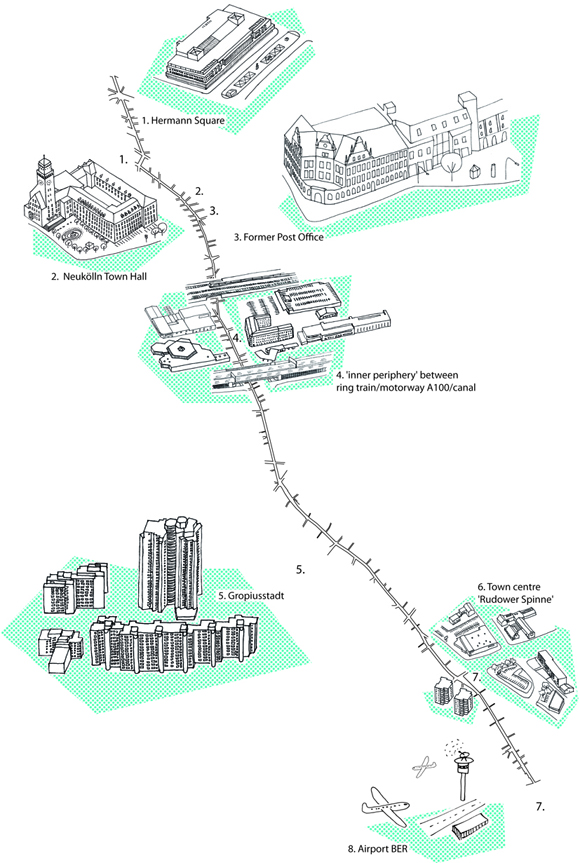

2. A GIGA-MEGA-SIZE REAL ESTATE DEVELOPMENT: MEDIASPREE

’As far back as the early 1990s, city planners began discussing ways to utilize and develop the left and right banks of the Spree River in the former East Berlin in an area that was once divided by the Berlin Wall. They prepared draft plans and a land-utilization scenario, which succeeded in attracting the interest of real-estate developers. With almost €60 billion in debt, Berlin needed money. At a certain point, the city, landowners and investors formed an organization to market the riverbanks. They called their group 'Mediaspree'.5 5. Christoph Scheuermann. 'Building Spree: Developers and Dreamers Battle Over Berlin Identity'. – Der Spiegel. Sept 11, 2008

6. Jennifer Gardner. 'Berlin Mediaspree' – Cargocollective. June 2010

’In short, ’Mediaspree’ is the branded vision created by a coalition of property owners, developers and investors, intended to promote the development of the Spree’s upland areas in the Kreuzberg and Friedrichshein neighbourhoods of Berlin as Germany’s newest media center.’6. The plans were based on earlier predictions of immense population growth of Post-Wall-Berlin, thought to soar from 3.5 million to 6 million, beyond even pre-Second World War dimensions! Such a growth allegedly required an appropriate supply of office and living spaces. In reality, this never happened and the population of Berlin is still around 3.5 million, with a mild upswing of 100.000 to 200.000 in the coming years.

Due to Berlin ́s dire financial situation, the Mediaspree plans – drafted in the 90's – have been only partly implemented. It has been using the tactics of ’nice regeneration’: reusing old industrial buildings, bringing in creative industry and opening culture institutions such as galleries, restaurants, and event spaces. But the main characteristic of the place is defined by the completed super-modern glossy monoliths: headquarters of MTV Networks Germany, Universal and VIVA, accompanied by ’other out-of-scale scale developments like the 17.000-seat O2 Arena.’7 7. Ibid.

Next to the new buildings there can still be found ’a protected but neglected historic industrial compound, an established anarchist squatter community, [...] residences of a primarily German-Turkish population’.88. Ibid.

The Mediaspree area: green – existing buildings; red – planned new buildings; hatch – 50 metres wide area along the riverbank

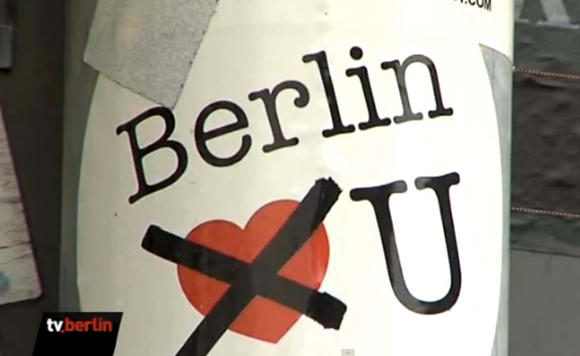

3. CITIZEN PROTESTS – ‘SPREE RIVERBANK FOR ALL’

Mediaspree development turned out to be the one common denominator that united most urban groups – urban activists, clubbers, green politicians, members of the underground, neighbourhood associations, anarchists etc. ’The entire project is perceived as an investment in the high-end sector, primarily about profitable river front development with a privatized view of the river Spree, while the social realm is neglected. It is feared that the planned ‘valorization’ of the area will lead to rising rents, anti-social urban development, and cultural extinction.’9 9. WikipediaAnd ’with the program Mediaspree, some of the most popular free spaces along the Spree’s riverside are condemned. These alternative bars, beach areas and parks are so much part of their air and Berlin’s soul.’1010. Urbalize article, based on www.ms-versenken.org Due to those fears, protests increased, culminating with large demonstrations by the initiative ’MediaSpree versenken!’ (Sink MediaSpree!), active since 2007.

Investorenbejubeln (Investors' Celebration), a demonstration on the river Spree in which protesters used rubber dinghies and paddle boats to follow a boat-cruise of Mediaspree investors, which was then broken off prematurely (Wikipedia)

After gathering several thousand people in the course of different protests, under the common slogan ’Spreeufer für alle!’ (Spree riverbanks for all!), the core members of the resistance movement launched a petition for a referendum. Their goal was to publicly decide on the following aspects of the Mediaspree development:

– A 50 meter buffer zone of free space along the river banks (instead of proposed 10 meters)

– Keeping the standard Berlin 22 meter height restriction applicable to new buildings

– A new bridge built only for cyclists and pedestrians, not cars

The necessary supporting signatures were collected quickly and on 13th of July 2008 the referendum took place. 87% of voters – roughly 30,000 people – supported the proposals of Sink Mediaspree. According to the organization Mehr Demokratie (More Democracy), this was the most successful Berlin citizens movement to date.1111. Wikipedia The results were not binding, however, and city officials expressed different views whether the public opinion would be taken into account. For 15 months The Special Committee Spree, formed of different stakeholders, deliberated. By then the protesters had announced the following:

’The achieved alterations to the designs (see info brochure), however, did not indict a real breakthrough or change in direction. Demands of the referendum for a minimum 50 metre gap between the river front and new developments, the renouncement of high rises and car traffic bridges were still not met! Hence, we continue to fight for an alternative, social and ecological urban development that is open to the involvement of many, not just of a few building speculators. One first step has got to be a stop to the sell-out of the last remaining publicly owned land. We demand: (Re)municipalisation now!’12 12. ”Sink Mediaspree” homepage

MORE ABOUT THE MEDIASPREE DEVELOPMENT AND THE OPPOSITION TO IT IN DER SPIEGEL ARTICLE.

THE ’SINK MEDIASPREE’ HOMEPAGE is a source of information on civil protests (don ́t miss out on the brochure).

4. Bar25 -> KATERHOLZIG

'By chance the ‘Bar25's location was right in the middle of the Mediaspree project's development area, and the owners (Berlin Sanitation Service) had plans to capitalize on it. The lease period was going to end in the winter of 2008, so Bar25 held a big closing party in September 2007.’13 13. Luis-Manuel Garcia. 'Showdown in Spreepark'. Nov 26, 2010They moved out only in 2010, though, after an eviction notice, illegal squatting of the place during the summer and a temporary settlement with the landlord.

‘What's curious about this is that Klenzendorf had made a big deal about the impermanence of Bar25. In several interviews, Klenzendorf insisted that much of the specialness of the place came from the fact that it will soon close, that he'd rather end it before it got stale. In Tobias Rapp's ’Lost and Sound: Berlin, Techno, and the Easyjet Set’, for example, Klenzendorf is quoted giving his opinion on the inevitable closing of Bar25, saying: 'At some point, it'll all be over. But it's also beautiful that it's so transitory[...]. A fantastic time. A closed chapter. That's how it'll be, and I think that's great.'

But by the summer of 2010, the philosophy had shifted. Bar25's management was considering re-opening in a new location; a website dedicated to 'saving' Bar25 from closing came online; and Bar25 and a group of filmmakers have been collecting money online to create a documentary about the place. Suddenly, Bar25 went from having a Zen-like acceptance of its finality to running in three directions: preserve the magic on film, prevent the closing altogether or start afresh in a new place.’14 14. Luis-Manuel Garcia. “Showdown in Spreepark”. Nov 26, 2010

During Sink Mediaspree protests (YouTube)

A still from the ‘Bar25 - Tage außerhalb der Zeit’ movie by Britta Mischer & Nana Yuriko 2012. ’Worlds away from society's conventions and norms, Bar25 became the melting pot from which a truly Berlin culture emerged. The film follows the creators of Bar25, four young individuals whose free-wheeling way of life, of music, individuality and never ending energy transforms a riverside wasteland into a fantasy land by the river Spree. But if the community's life appears fulfilling from the outside, living it day after day isn't easy. With this rhythmic and colorful film we aim to show viewers the diversity, internationality and creativity of Berlin and what it takes to create a seemingly utopian world.’ (IMDB)

As a result, a new place, KaterHolzig , was opened just across the river, on a plot of an old soap factory. Also with a short lease, KaterHolzig is by now as legendary as its predecessor. Besides the (now year-round) club there ́s a daytime bar, restaurant and ’hand-built adventure playground’15 15. Tobias Rapp. 'Showdown on the Spree: Cult-Bar Site Symbolizes Battle over Berlin's Future'. – Der Spiegel, June 13, 2012

16. Skrufff. 'Berlin’s Christoph Klenzendorf - Beyond Bar 25 & Katerholzig (an Interview)'. Nov 26, 2012. As Klezendorf explains: ’My partner is a really good chef and we did this high class kitchen which also attracted really different people. So all the ravers came but also people who could afford to spend 30 EUR each on a steak. And they all mixed up together and everyone enjoyed it. Which was why so many different types of people started coming.’16

5. Bar25 -> KATERHOLZIG -> HOLZMARKT & MÖRCHENPARK

KaterHolzig will close in the autumn of 2013, but in the meantime their ideas have reached new heights. ’We want to develop (the idea that started with) Bar25 to the next level. It’s never going to be the place it was before, it will never be a full-on hedonistic party temple, but we want to bring the spirit of Bar25 and the network of people who developed that idea and develop the site involving them.’1717. Ibid. In the summer of 2012 (and ‘conveniently coinciding with the release of the documentary’ 1818. Luis-Manuel Garcia. 'Another Post-Bar 25 Update'. June 22, 2012) KaterHolzig organisers announced the opening of two parallel projects that they hoped to build on the old Bar25 premises: Holzmarkt and Mörchenpark.

Holzmarkt is built around the concept of a live-in community: a hotel, an IT-centre, a student dormitory with 400 apartments, a 18.000 sq m village of artist studios (most of which will have rolling three-month leases to keep things fresh), a restaurant and a 24-hour day care centre with space for 30 kids.

Mörchenpark will be a child-friendly public park that uses German fairy-tale themes while also providing wholesome, nature-oriented activities for children.

The concept is that ‘we combine nature, economy and culture in our thoughts and considerations. [...] Where the scar between East and West is still visible, a vibrant neighbourhood that connects Friedrichshain and Kreuzberg is to be created.’1919. holzmarkteg.de/seite/?/en Or to put it another way – ’the clubbers want nothing less than the future of life. Ecology, global food security, alternative energy, mobility... It will be an experiment of subculture, labour and urban development’.20 20. Karin Schmidl. 'Das Dorf der Zukunft'. – Berliner Zeitung, October 19, 2012

FOR MORE, SEE THE BROCHURE (pdf) explaining the concept of Holzmarkt in detail.

6. THE BID

Fundraising begins for both projects, jointly called the Holzmarkt, via an upcoming public auction for the old Bar25 location.

Berlin's government is ’notoriously cash-strapped, and has been for years’2121. Dan Hill. 'Journal: A walk in Schöneberg, Berlin: energy policy, gentrification, protest, and the humble joys of communal flower beds'. May 07, 2012

22. Tobias Rapp. 'Showdown on the Spree: Cult-Bar Site Symbolizes Battle over Berlin's Future'. – Der Spiegel, June 13, 2012, so the selling of public land has been an important source of income. Yet in the last 10 years, Berlin has almost always sold its properties to the highest bidder. This situation has created mounting criticism – ‘many fear that without the necessary open space, Berlin could soon say goodbye to the only major success story of recent years: its booming cultural scene’22.

In the case of Holzmarkt their ‘grass-roots-style, anti-commercial, communal, and Mediaspree-critical approach has caught the attention of much of the media. They’ve rather cleverly put a lot of public pressure on the city by making their building proposal the moral favorite for the public, even if it’s not the economic favorite.’2323. Luis-Manuel Garcia. 'Another Post-Bar 25 Update', June 22, 2012

24. Tobias Rapp. 'Showdown on the Spree: Cult-Bar Site Symbolizes Battle over Berlin's Future'. – Der Spiegel, June 13, 2012 But the public support alone won’t be enough to win a bid for 18,672 square meters (about 4.6 acres) of prime real estate, which is about the size of three football fields24.

Luckily, Berlin didn’t have to weigh the value of the culture industry – thanks to Swiss legislation, the Holzmarkt people ended up placing the highest bid.

In Switzerland ’since 1985, all residents are required to make provisions for old age. 2500 pension funds manage the savings of individuals or groups of companies, which pay for employees.’ One of the founders of Stiftung Abendrot (the Eclipse Foundation), who became the owner of the former Bar25 property, explains: 'We prefer to buy brownfields and then support ecological and culturally significant projects. That can be sheltered workshops or spaces for artists and craftspeople. Two months ago, Eclipse has acquired an old subway station in Wedding. It has been developed into the 'Cultural and historical centre of Christiania'25.25. Karin Schmidl. 'Das Dorf der Zukunft'. – Berliner Zeitung, October 19, 2012

26. Ibid. The purchase price must be earned back but he adds: 'The constant race for profit destroys society. The agreed rent is moderate enough for us.'26

The location has been contractually passed on to clubbers in order to bring the Holzmarkt idea to life. Christoph Klezendorf explains that ’by planning in a huge hotel that made it possible for us to bid the high amount for the land we needed to. The building is going to be a 32,000 square metre building that’s 30 metres high and it will be behind the railway tracks [...]; it’s 6,000 square metres that faces the street. There will be student accommodation and also a business/research centre for start-ups’2727. Skrufff. 'Berlin’s Christoph Klenzendorf - Beyond Bar 25 & Katerholzig (an Interview)'. Nov 26, 2012

28. Ibid., all forming a self-sustaining part of Holzmarkt. ’The whole idea is that it will be a research centre with people living and working under the same roof, researching into the future, on how to optimise our society and how we stop wasting resources.’28

This will also help to sustain the other cultural events taking place. ’The goal is that the cultural elements of the club can be sustained easily without needing too much money. Whenever you put a lot of financial pressure on a cultural project the creativity is reduced and we hope to remove that pressure.’29 29. Ibid.

View of KaterHolzig from Holzmark site. Photos: Regina Viljasaar

Spree river: on the left bank in haze KaterHolzig, on the right bank Holzmarkt's site

Example of Mediaspree reconstructed and new buildings

7. THE FUTURES

Holzmarkt has begun a new strategy for realising their visions while also compensating the Foundation Abendrot for their investment. An estimated €50 million is needed to make the entire project happen.3030. Tobias Rapp. ’Showdown on the Spree: Cult-Bar Site Symbolizes Battle over Ber- lin's Future’. – Der Spiegel, June 13, 2012 To reach that goal, a cooperative has been formed - Genossenschaft für Urbane Kreativität (GuKeg) - where anybody can take part in creating both economic and public value, providing a generous amount of money is invested. The management of this project has been crafted following open and participatory values; a ’corporate structure (see pdf) to separate the power of money from the power of the voice’3131. Ibid. has been worked out.

At this moment the cooperative is busy with finding new members and investors. According to their latest news the money hasn’t been flowing in as quickly as required3232. 'Holzmarkt-Projekt droht zu scheitern'. Berliner Zeitung, January 28, 2013

33. Karin Schmidl. 'Genossen dringend gesucht'. – Berliner Zeitung, January 28, 2013, but ‘clubbers who turned real-estate and culture managers’ promise that work will begin on the site in the spring33.

The plan is to start by:

’building up a temporary container city to use when we’re still constructing the site, for the restaurant, theatre and party events. The idea is to start with temporary buildings, which become permanent [...] gradually. We have a time period of 99 years to develop the project [...] – longer than we will be around for, so that’s also the nice thing about the project. We can develop it for our eternity. That’s the main difference to all of our earlier projects because we always knew we had to tear everything down that we’d built up. [...] We anticipate it will be partly finished within two to three years. And when I say ‘partly’ it’s because we never envisage it being totally finished, we’ll never stop developing. There should always be new rooms, ideas.’34 34. Skrufff. 'Berlin’s Christoph Klenzendorf - Beyond Bar 25 & Katerholzig (an Interview)'. Nov 26, 2012

The story of a club that keeps jumping over river and growing in its ambition is not an easy one to understand. A foreign pension fund investing in culture is not a completely uncommon thing – even Telliskivi Creative Campus, where one of the authors of this overview spends her working hours, started like that. But the symbiosis of completely different activities and running models in a ongoing large-scale development is what makes this project most interesting.

veeb.jpg)