U asked Helsinki residents for their opinions on the liveability of the city. The expat’s perspective is often more contextualised and unique for evaluating processes from an outsider viewpoint.

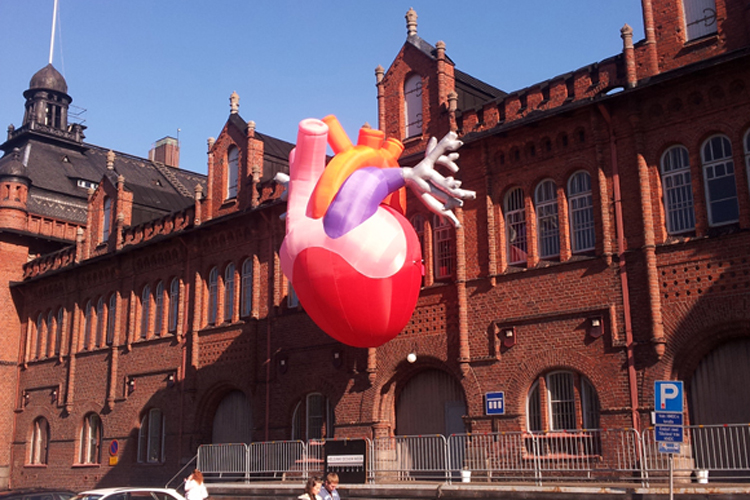

Emblem of Helsinki design week 2011 'Wild at Heart' by Andy Best and Mirja Puustinen. All photos by Kristi Grišakov

Yearly Vappu celebrations - putting graduate hat on Havis Amanda sculpture

Vallila - one of Helsinkis remaining wooden districts

Otaniemi campus pop-up sculpture

Laituri - urban information center

Aarrepuisto awarded neighborhood park, Vesala, East-Helsinki

Kristi Grišakov

Helsinki-Tallinn twin-citizen since 2006

No city is ever perfect or “ready” in the mind of its citizens, no matter how liveable it might seem by quantitative standards. There is always a problem with crazy bureaucracy, being under- or over regulated, expensive, without affordable living spaces etc. For me a liveable city is a place where I can concentrate my energy on actual living (work and hobbies), where the surrounding urban environment and connected services are supporting, not hindering it. Based on this definition, Helsinki is liveable. It can be compared to a grown-up who is successful, polite and conscientious, supports her family, honours certain traditions, has strong (sometimes rigid) principles, enjoys culture and appreciates simple and local design. However, all of that doesn’t mean one shouldn’t go to the sauna naked and get drunk once in a while. All in all, as a citizen you feel safe and secure relying on that sort of a person. These qualities reveal themselves in every aspect of Helsinki's life, although they appear sometimes so seamless that there is a danger they can go unnoticed. Good city planning is like special effects in the movies – it is almost unnoticeable, if well done. In this case Helsinki is a good stuntman and a computer wizard – public transportation is running like clockwork, people are helpful and don’t cut queues, the public spaces are cozy and offer a variety of activities for all age groups. The city itself, regardless of its urban sprawl, is forming an interconnected network of roads, trails and passes for all movement preferences. Although some aspects of urban planning are heavily regulated, the usage of public space for a variety of activities is still encouraged (to play games, have a picnic or just sleep on the grass). Overall, Helsinki is comfortable for its citizens not the other way around.

Happihuone

Punavuori

Happihuone

Kannelmäki

Kannelmäki

Kannelmäki

Kannelmäki

Malminkartano

Malminkartano

Malminkartano

Malminkartano

Malminkartano

Pasila

Andrew Gryf Paterson

Artist-organiser, independent researcher

As an immigrant from North-west Europe, growing up in Scotland, I have about 10 years experience living in post-industrial towns and cities in the UK. I based myself in Helsinki at the beginning of 2003, as a particular kind of expat: I came to study and stayed, as an artist, researcher, cultural worker and networker. Comparing Helsinki to urban places I knew, Helsinki is a city where things are growing, more organised and efficient, that is very active as a culture-supporting capital city for its size, as well as feeling safe and 'stable'. For many years Helsinki has happily been my professional 'base' in the Eastern Baltic Sea Region, and I have gained lived experience of the city in two ways.

In my early years, as a single guy in a single room apartment on the edge of downtown 'trendy' Punavuori, I knew I was a in a good location, but sometimes wished that the city was not so stable and efficient, more random and playful. At that time I travelled a lot and rarely had a chance to settle. Around 2005 I came across the extraordinary cultural greenhouse 'Happihuone' on Töölönlahti, first built during European Capital City of Culture 2000, which gave me an insight into grassroots ecological and subcultural scenes. However, my urban experience was frequently supplemented with travels, for example to Riga, Berlin, London, Glasgow..

Later in a transitional year, I had longer residencies in Barcelona, Istanbul, Chicago, and New York, which gave new ideas and comparative examples of cultural gentrification and counter-activism, urban gardening and autonomous cultural centres. Reflecting, I went searching to find the types of things which I was hoping to find in Helsinki. Then I returned, let’s say, to my 'second Helsinki life', in 2007, when I moved into a family situation in the Northern suburbs of Kannelmäki. At the same time 'Happihuone' was dismantled by direction of the city planners. However, the next summer, NGO Dodo initiated and promoted urban gardening at other spots in the city, and I watched with interest to see how things would develop onwards.

So I am still in the northern suburbs 5 years later, but a little further outwards in Malminkartano. I have an appreciation of different things in the city: I have gained neighbours that I know, backyard facilities with social relations, an allotment plot nearby, and a young child. However, I am still wishing that the suburbs were a bit less stable, had some visible energy with people on the streets: A self-organised social, cultural or community centre space to meet others. A cafe would be nice. Many street-front units in my neighbourhood are either hairdressers/beauty salons or small engineer-entrepreneur offices. Dare I say, I wish for something more lively. Where would I be without the Internet?

Now a more established member of the cultural and grassroots scenes of Helsinki, I have followed the creative energising of the city taking place, for example in Kallio, Vallila, and temporary Kalasatama in the last couple of years. But these are still a bit far from where we live, eat dinner, and sleep. I wonder how long before alternative and world design (or cultural) capital vibrations shake Helsinki's outer suburbs like mine.

Inhabitants include older-generation working and middle class residents, mixed with younger couples and families moving here for extra space and maybe some quiet. Finns live among immigrants such as Western Europeans like myself, as well as repatriated Karelians, nearby Estonians, Russians, far-travelled Somalis, Afghanis and others. This multi-cultural and multi-ethnic image is created from people whom I can see and hear in my apartment block and neighbourhood, walking to and from the local commuter railway station. How and where can this suburban population get to know each other? How will older and newer neighbourhood activist energies meet? Will it be Restaurant Day or Cleaning Day, or some other creatively invented occasion? I look forward to a common space for us all to drink coffee or tea, bake, make, listen and learn from each other, fix and experiment in the unstable future predicted ahead. In the last year I’ve been making little steps in this direction, dreaming of a very local, grassroots artist-residency for myself where I live.

Photo: Mikko Kallionsivu

Jenni Kallionsivu

Programme leader of the Finnish Institute

I'm a Finn whose relationship to Helsinki is strongly based on Tallinn. I have started to visit the capital of the country of my birth only after moving to work in Estonia. Helsinki is actually like a northern part of my current home town Tallinn. Very expensive, but still. I don't have the statistics, but I think that an average Tallinner goes to Helsinki more often than an average Finn from the North. When I moved to Tallinn from Tampere (which is not really an example of Northern Finland), my friends from Helsinki were delighted, that they can visit me cheaply. The boat ticket is much cheaper than the train ticket to Tampere, a few hundred kilometres up north.

I could continue about how the Southern parts of Finland and Northern parts of Estonia are integrating to become one cultural- and economic space. And this has been talked about before. But in what language should we use to deal with our shared culture and economic business? English? Probably this is a great solution to many. After all, English is the contemporary lingua franca which you are expected to know in every position. But when there is more and more communication with the neighbours a feeling might emerge that it is a little bit bizarre to communicate in a language that is not native to either.

There is a considerable amount of communication already. In the old town of Tallinn during certain seasons you are more likely to hear Finnish than Estonian, and there are shops in the centre of Helsinki where the main language is Estonian. The reality of large cities is always multi-lingual and the connection between Helsinki and Tallinn can also be heard.

In this situation, knowing several languages becomes more and more important. I don't imagine a situation where every Finn expects Estonians to know Finnish. You can hear from the older generation that these situations have occurred and a reason has been given for these expectations. There is no point for looking a situation that would be the other way around. Not everyone has to know the language of their neighbours, if there is no need or interest. But I hope that we will continue to have a chance to learn each other's languages in need or will. In addition to everything good multi-lingual life helps to prevent dementia.